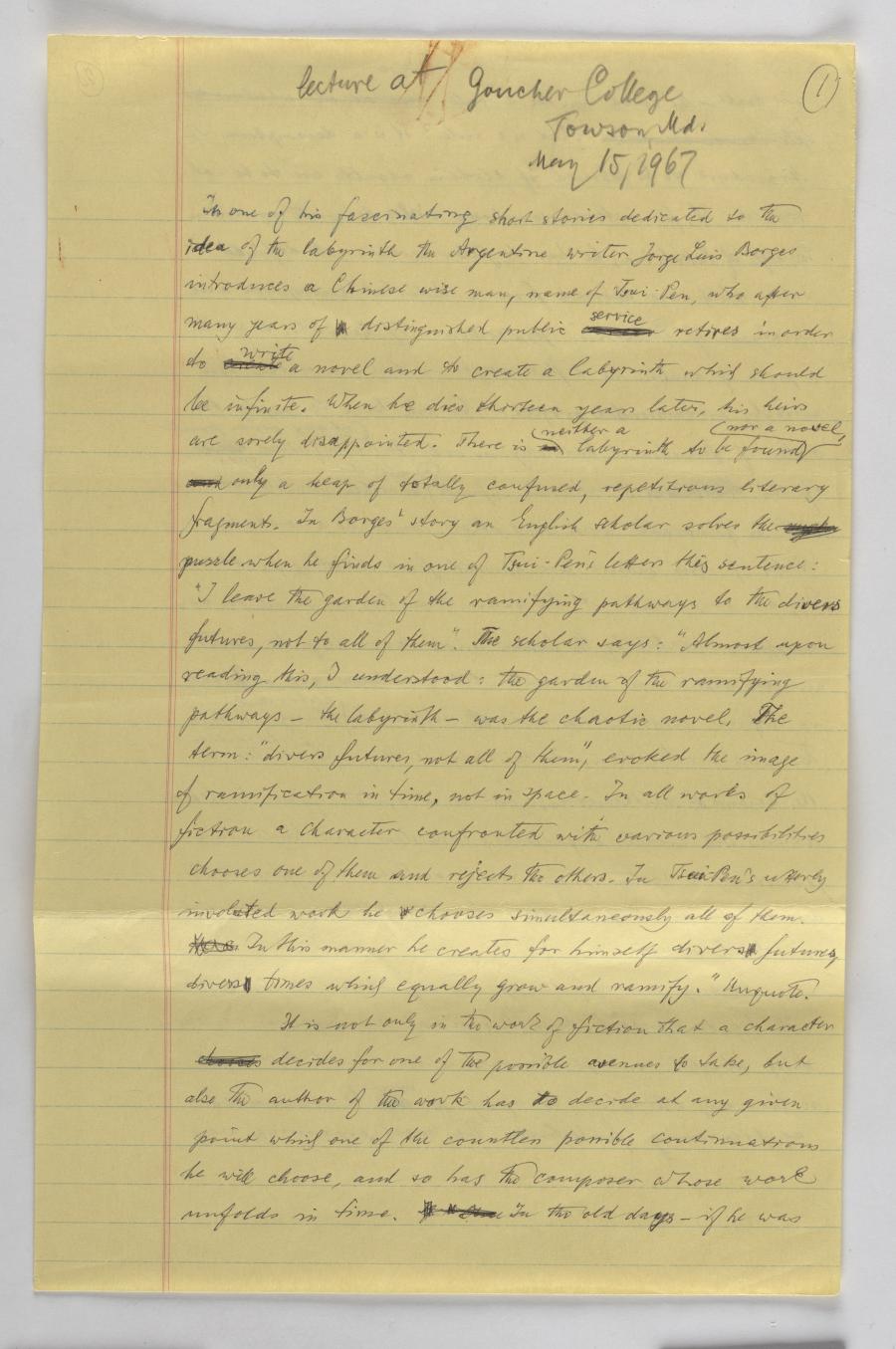

Lecture at Goucher College, Towson, Md. May 15, 1967

Abstract

Am 15. May 1967 hielt Krenek diesen Vortrag am liberal arts Goucher College, damals eine Universität ausschließlich für Studentinnen. In seinem Vortrag diskutiert er die dynamische und oft dialektische Beziehung zwischen (musikalischen) Regeln und dem kreativen Umgang mit diesen Regeln, zwischen Erwartung und Überraschung auf Seiten der Musik-Rezipienten, und wie sich diese Beziehungen im Rahmen der Neuen Musik, insbesondere dem Serialismus auswirken. Mit dem Schritt zum Serialismus hat die Musik letztlich ihren im traditionellen Konzertrepertoire verankerten sprachähnlichen Charakter aufgegeben und sich zu einer abstrakten Kunst weiterentwickelt. Die Anwendung strenger Prädetermination (oder auch Zufallsprinzipien) bei der Schaffung von Neuer Musik würde jedenfalls verhindern, dass Komponierende den Eingebungen ihrer Inspiration ausgeliefert sind, die Krenek als abhängig von sozialen und kulturellen Faktoren sieht.

Im Anschluss an den Vortrag dirigierte Krenek das Baltimore Symphony Orchestra in seinen Werken „Cantata for Wartime“, op. 95 und „Konzert für zwei Klaviere und Orchester“, op. 127.

1lecture at Goucher College

In one of his fascinating short stories dedicated to the

idea of the labyrinth the career create ee

It is not only in the work of fiction that a character

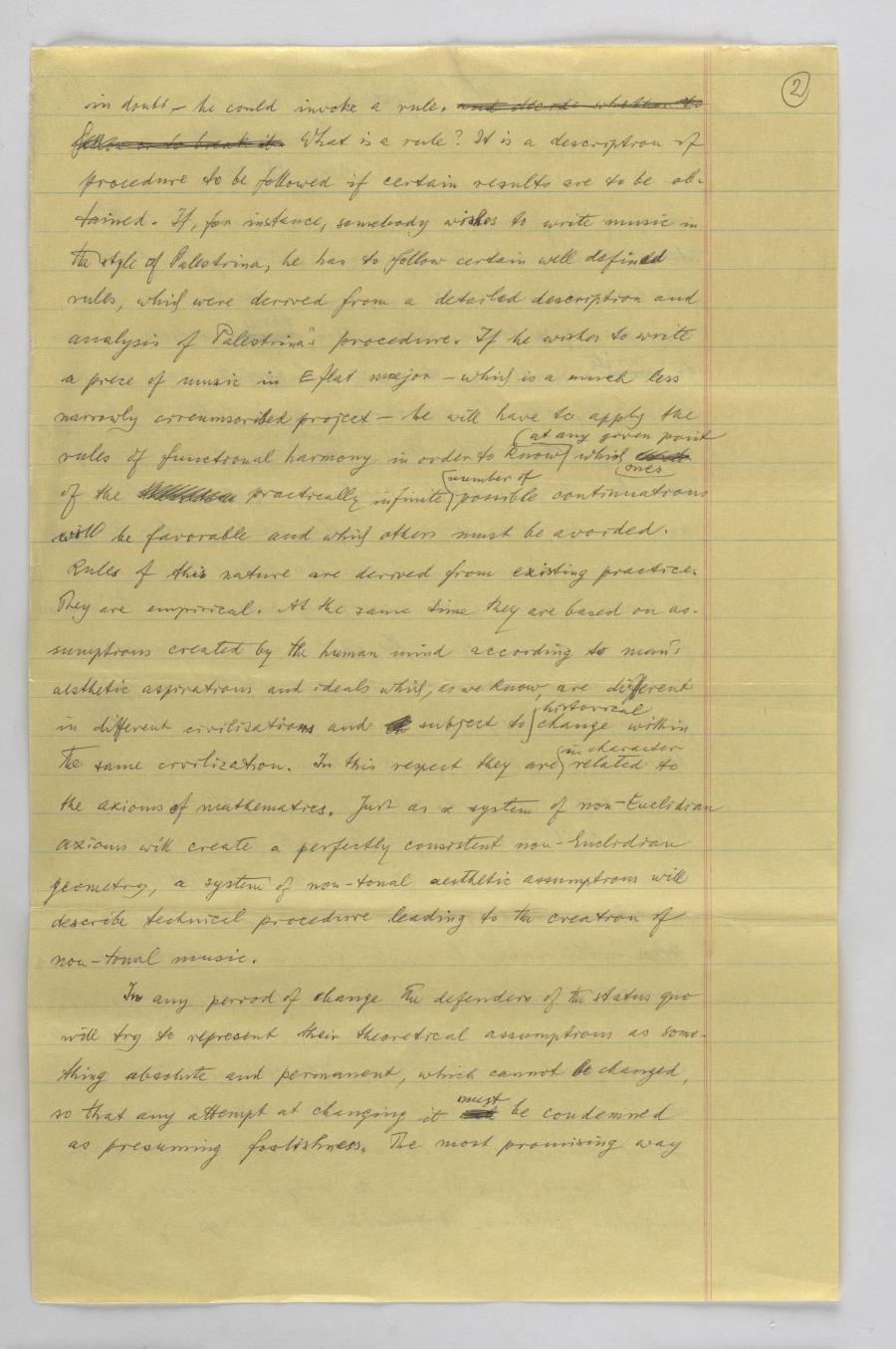

2

in doubt - he could invoke a rule. practically infinite

In any period of change the defenders of the status quo

will try to represent their theoretical assumptions as some-

thing absolute and permanent, which cannot be changed,

so that any attempt at will

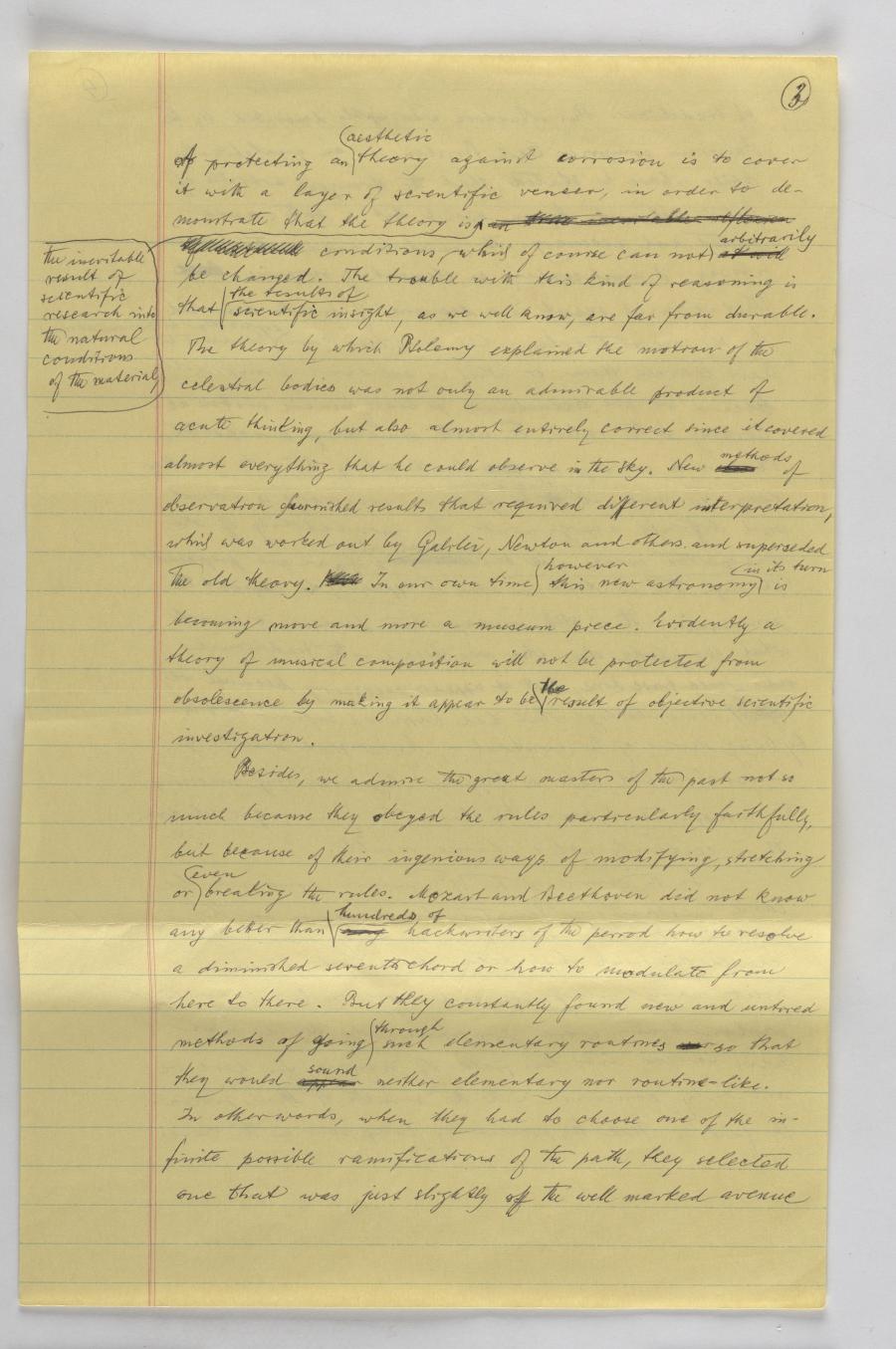

3

an inevitable reflexionat will

Besides, we admire the great masters of the past not so

much because they obeyed the rules particularly faithfully,

but because of their ingenious ways of modifying, stretching

ny hackwritersappear

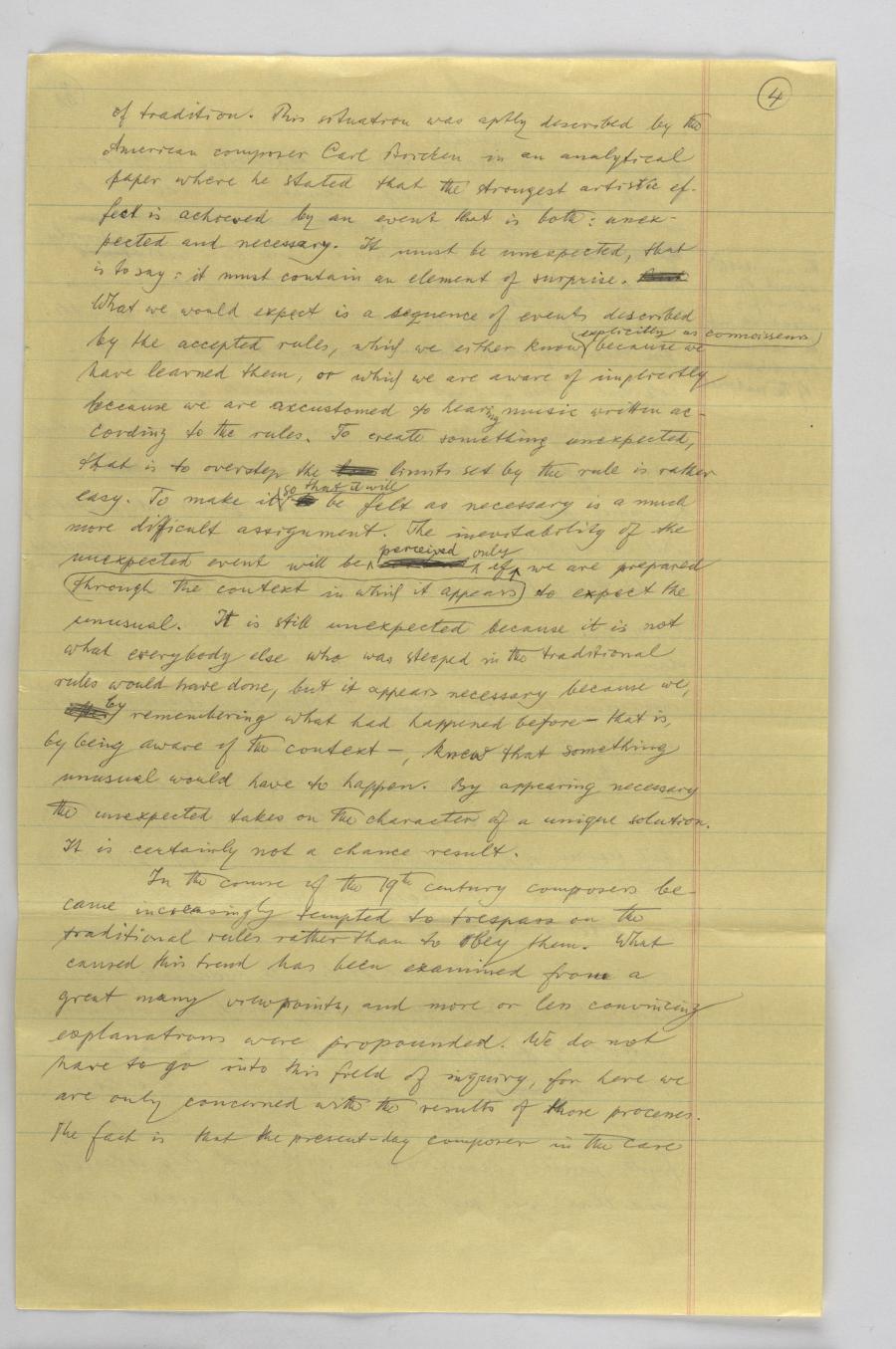

4

of tradition. This situation was aptly described by the

American composer be felt after

In the course of the 19th century composers be-

came increasingly tempted to trespass on the

traditional rules rather than to obey them. What

caused this trend has been examined from a

great many viewpoints, and more or less convincing

explanations were propounded. We do not

have to go into this field of inquiry, for here we

are only concerned with the results of those processes.

The fact is that the present-day composer in the case

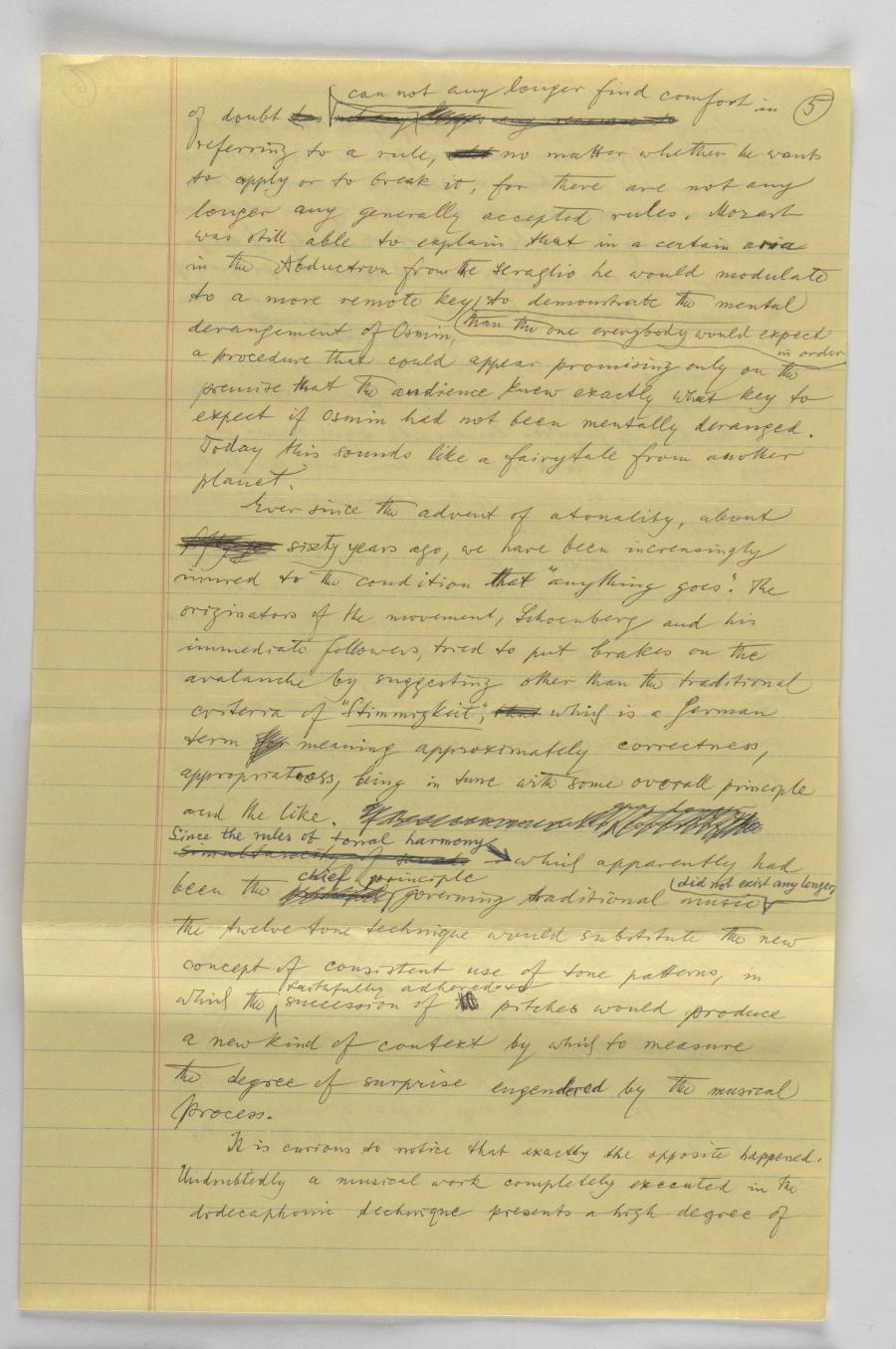

5

of doubt has not any any recourse to

referring to a rule,

Ever since the advent of atonality, about

Stimmigheit", simultaneity of sound principal the pitches would produce

a new kind of context by which to measure

the degree of surprise engendered by the musical

process.

It is curious to notice that exactly the opposite happened. Undoubtedly a musical work completely executed in the dodecaphonic technique presents a high degree of

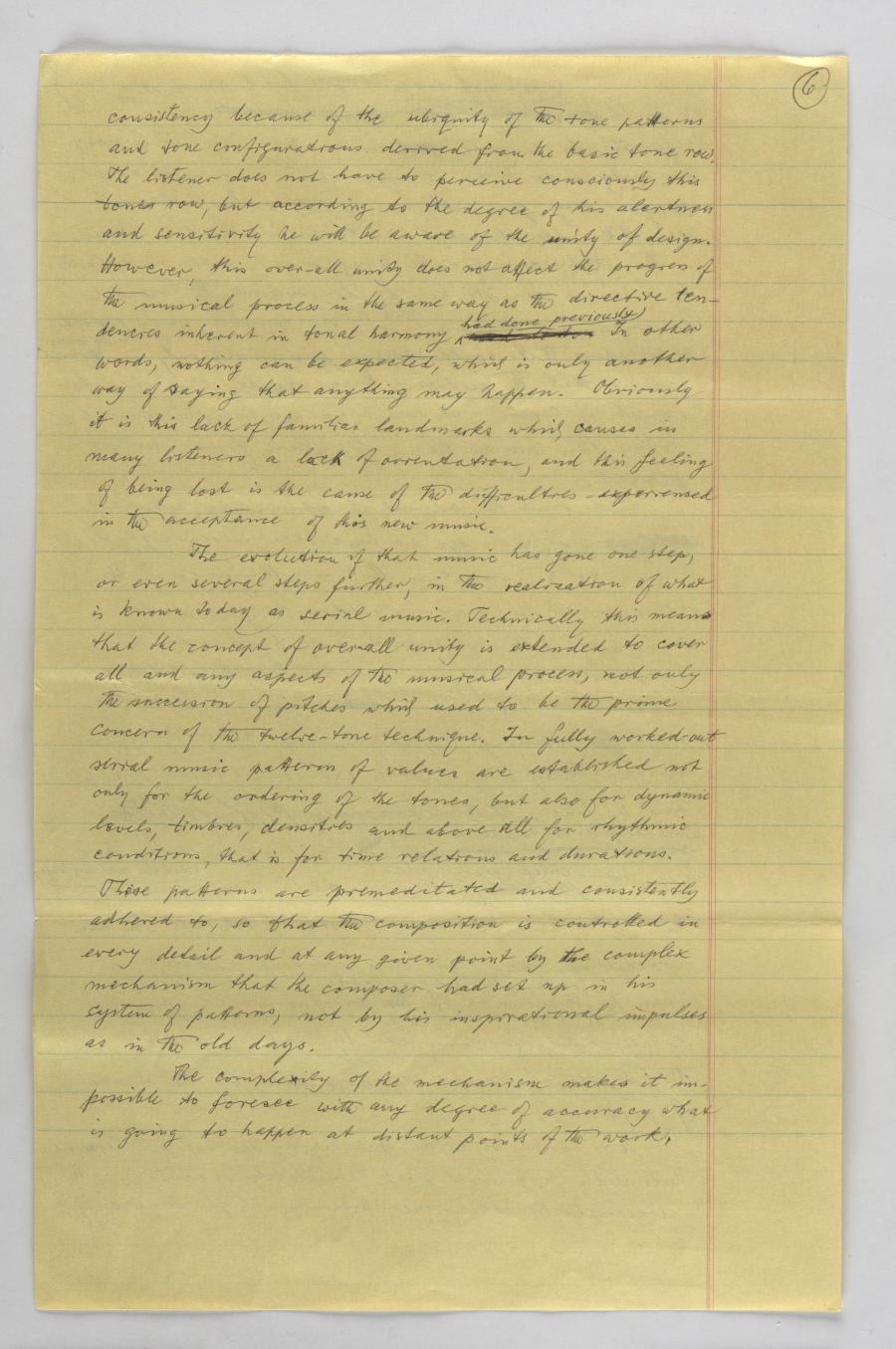

6

consistency because of the ubiquity of the tone patterns

and tone configurations derived from the basic tone row.

The listener does not have to perceive consciously this

s row In

The evolution of that music has gone one step, or even several steps further, in the realization of what is known today as serial music. Technically this means that the concept of overall unity is extended to cover all and any aspects of the musical process, not only the succession of pitches which used to be the prime concern of the twelve-tone technique. In fully worked-out serial music patterns of values are established not only for the ordering of the tones, but also for dynamic levels, timbres, densities and above all for rhythmic conditions, that is for time relations and durations. These patterns are premeditated and consistently adhered to, so that the composition is controlled in every detail and at any given point by the complex mechanism that the composer had set up in his system of patterns, not by his inspirational impulses as in the old days.

The complexity of the mechanism makes it im- possible to foresee with any degree of accuracy what is going to happen at distant points of the work,

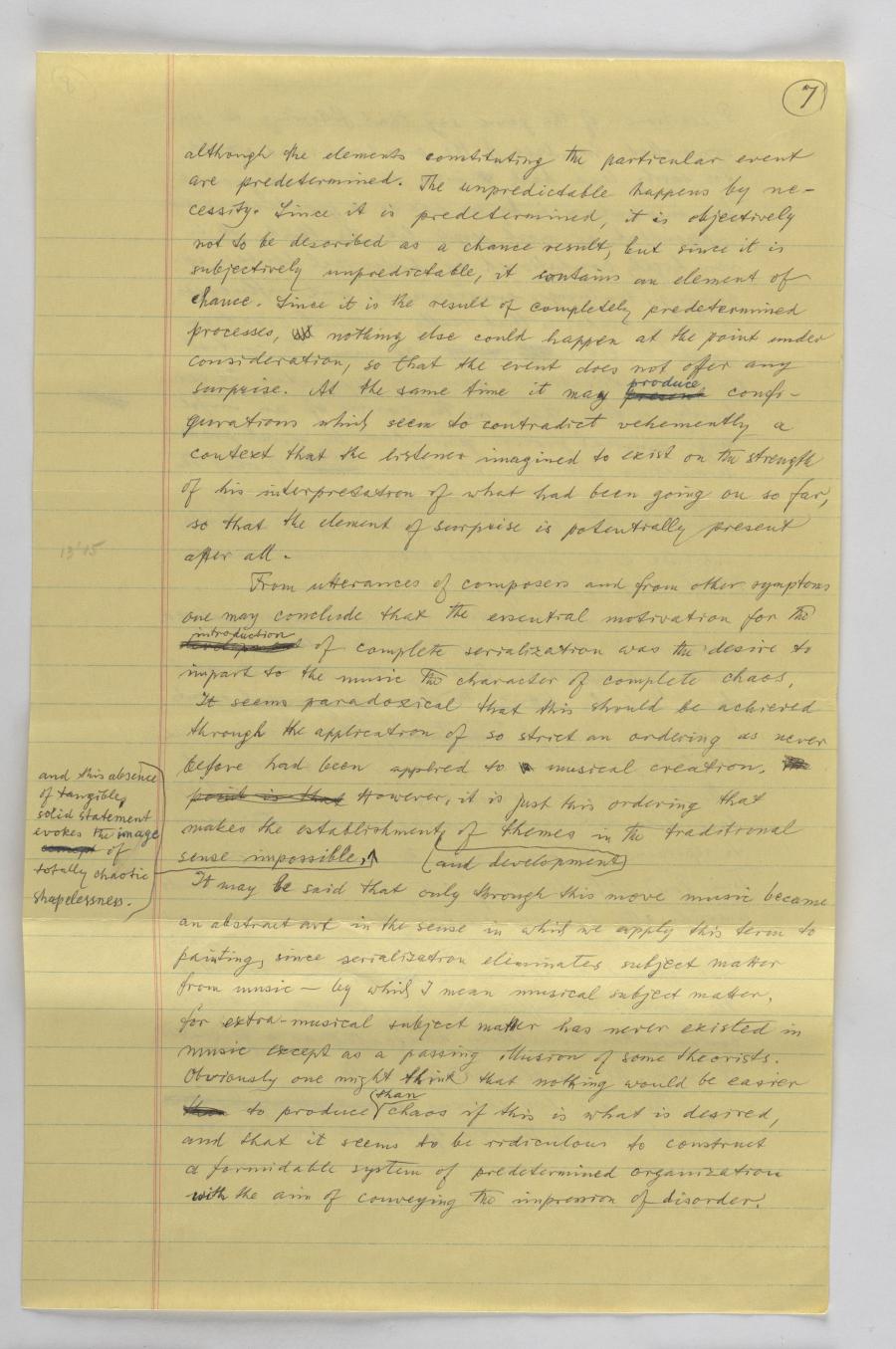

7

although the elements constituting the particular event

are predetermined. The unpredictable happens by ne-

cessity. Since it is predetermined, it is objectively

not to be described as a chance result, but since it is

subjectively unpredictable, it contains an element of

chance. Since it is the result of completely predetermined

processes, present

From utterances of composers and from other symptoms

one may conclude that the essential motivation for the

deployment

It may be said that only through this move music became

an abstract art in the sense in which we apply this term to

painting, since serialization eliminates subject matter

from music - by which I mean musical subject matter,

for extra-musical subject matter has never existed in

music except as a passing illusion of some theorists.

Obviously one might think that nothing would be easier

than to produce

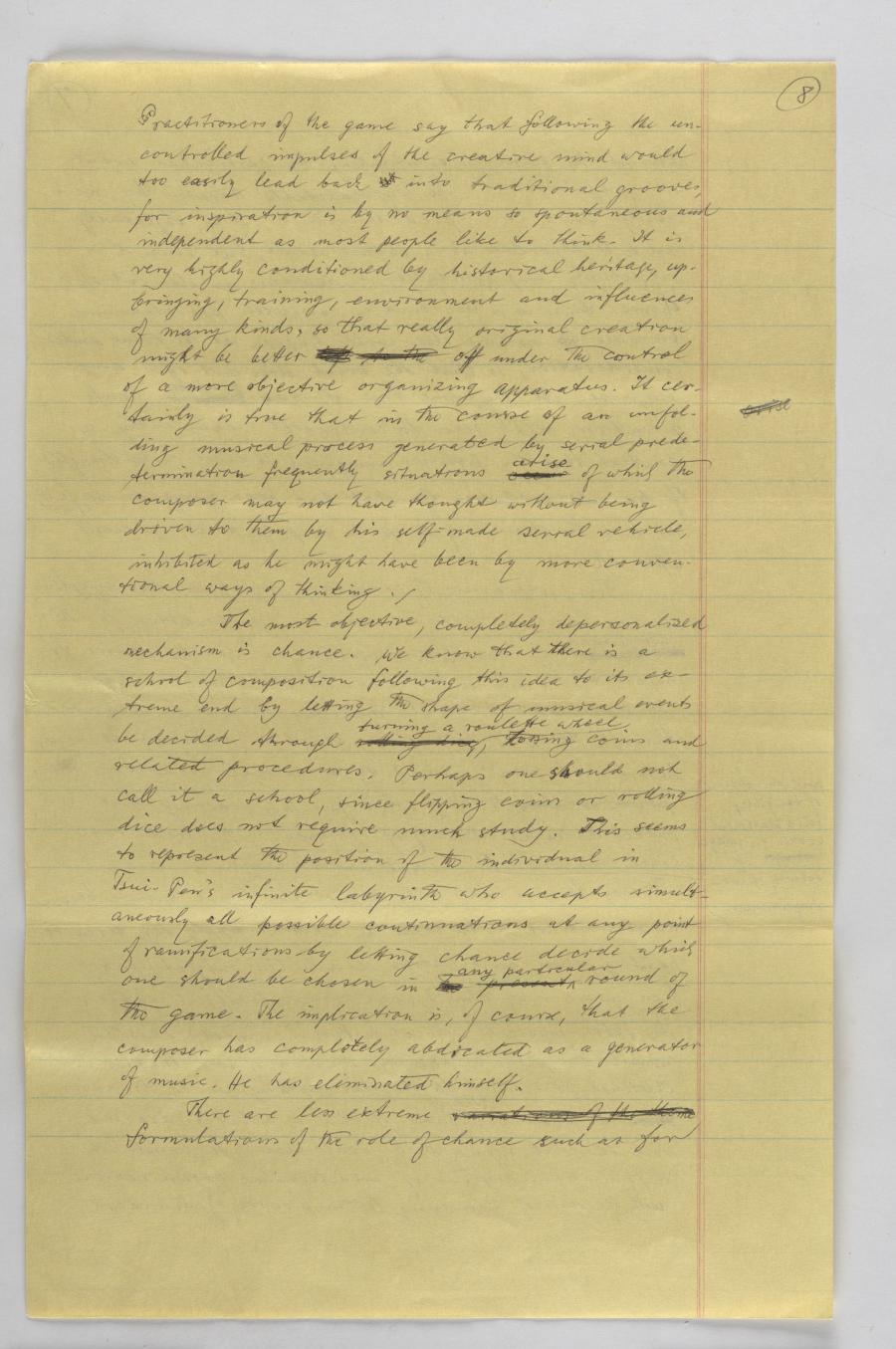

8

Practitioners of the game say that following the un-

controlled impulses of the creative mind would

too easily lead back occur

The most objective, completely depersonalized

mechanism is chance. We know that there is a

school of composition following this idea to its ex-

treme end by letting the shape of musical events

be decided rolling dice the present

There are less extreme

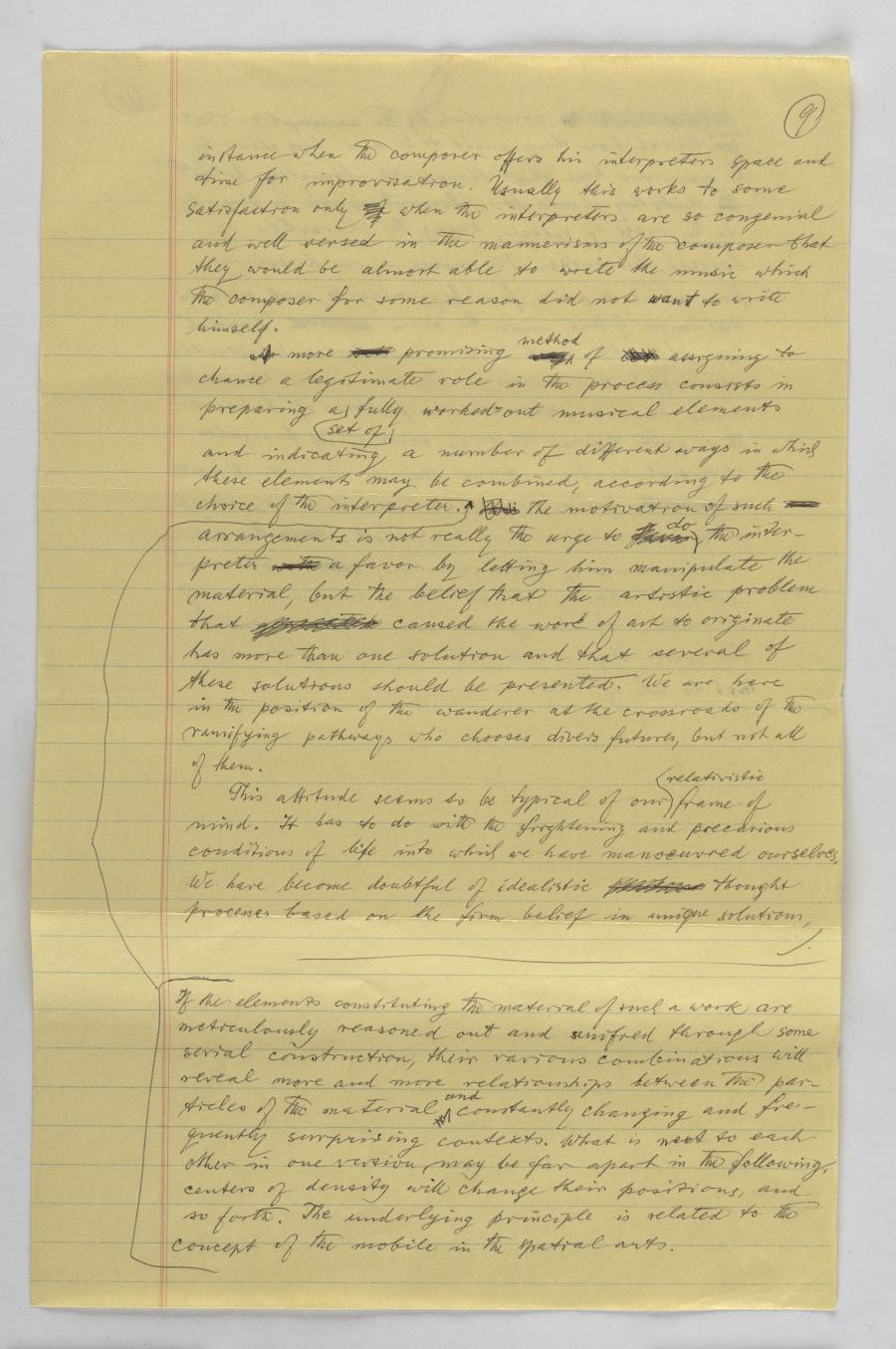

9

instance when the composer offers his interpreter space and

time for improvisation. Usually this works to some

satisfaction only

promising way assigningThisfavor

This attitude seems so be typical

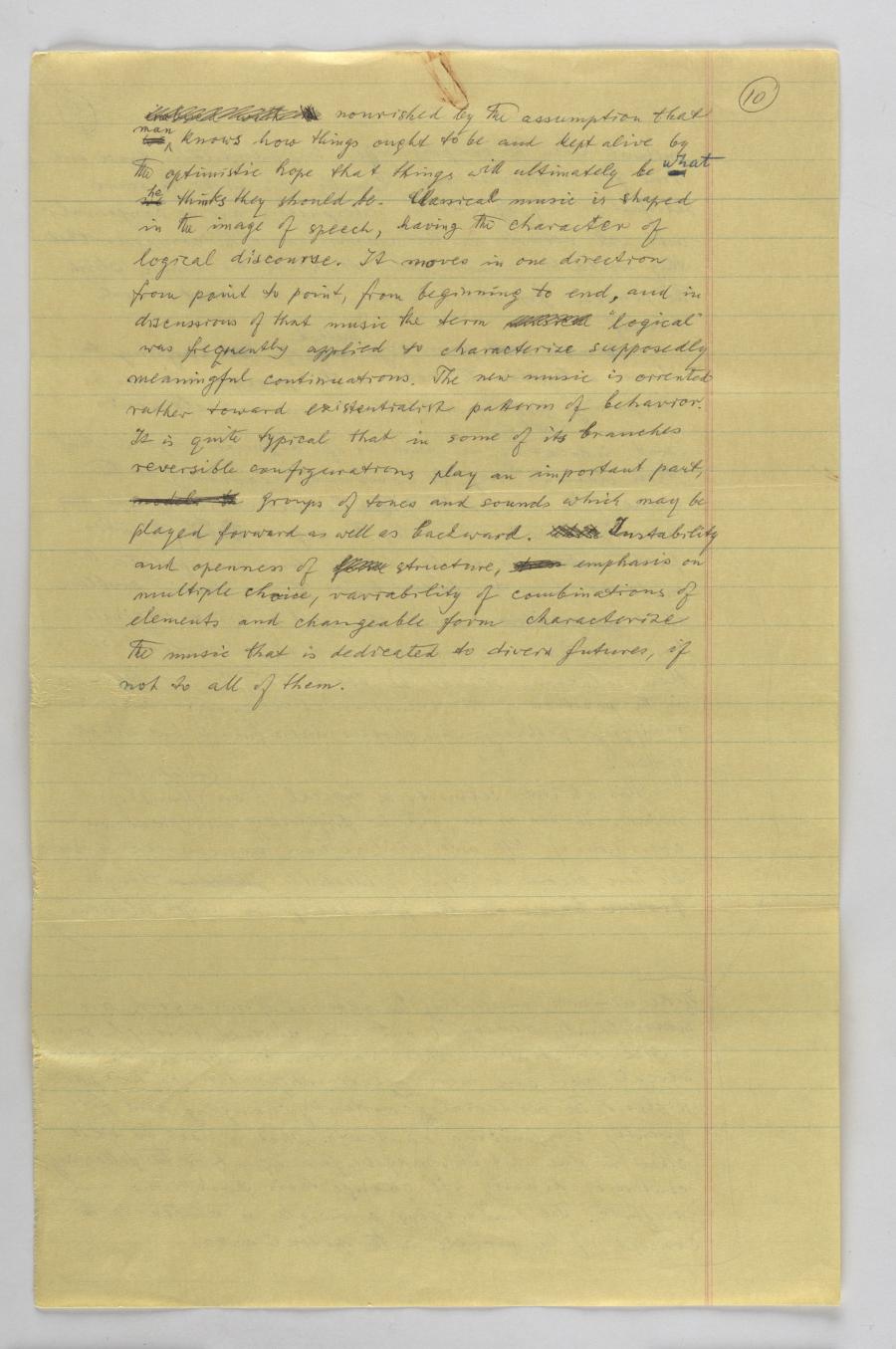

10

we we