A composer viewing this century's music. [UCSD Lecture I]

Abstract

Im Jänner und Februar 1970 war Ernst Krenek Regent’s Lecturer an der University of California, San Diego, wo er eine Serie von vier Vorträgen hielt unter dem übergeordneten Titel: „A Composer Viewing This Century’s Music“. Die Vorträge wurden jeweils Mittwoch abends gehalten und waren einer weit gespannten Themenpallette gewidmet.

In Krenek’s erstem Vortrag als Regent’s Lecturer an der UCSD, gehalten am 21. Jänner 1970, nimmt er in auto-biographischer Perspektive seine Entwicklung als Komponist in den Blick, wobei er die Stile seiner jeweiligen Schaffensperioden selbst in ihrer Beziehung zur historischen Entwicklung beziehungsweise zum selbstreflexiven Bewusstsein ihrer Historizität betrachtet.

Dazu gehört seine Phase des frei-atonalen Expressionismus, Neo-Klassizismus (insbesondere in Bezug auf seiner eigenen Schubert-Rezeption), seine Integration von Elementen der Unterhaltungsmusik in „ernste“ Musik, Annäherung Zwölftontechnik und seine Entwicklung darüber hinaus, in der er Inspiration von seiner Beschäftigung mit Musikgeschichte aufgenommen hat.

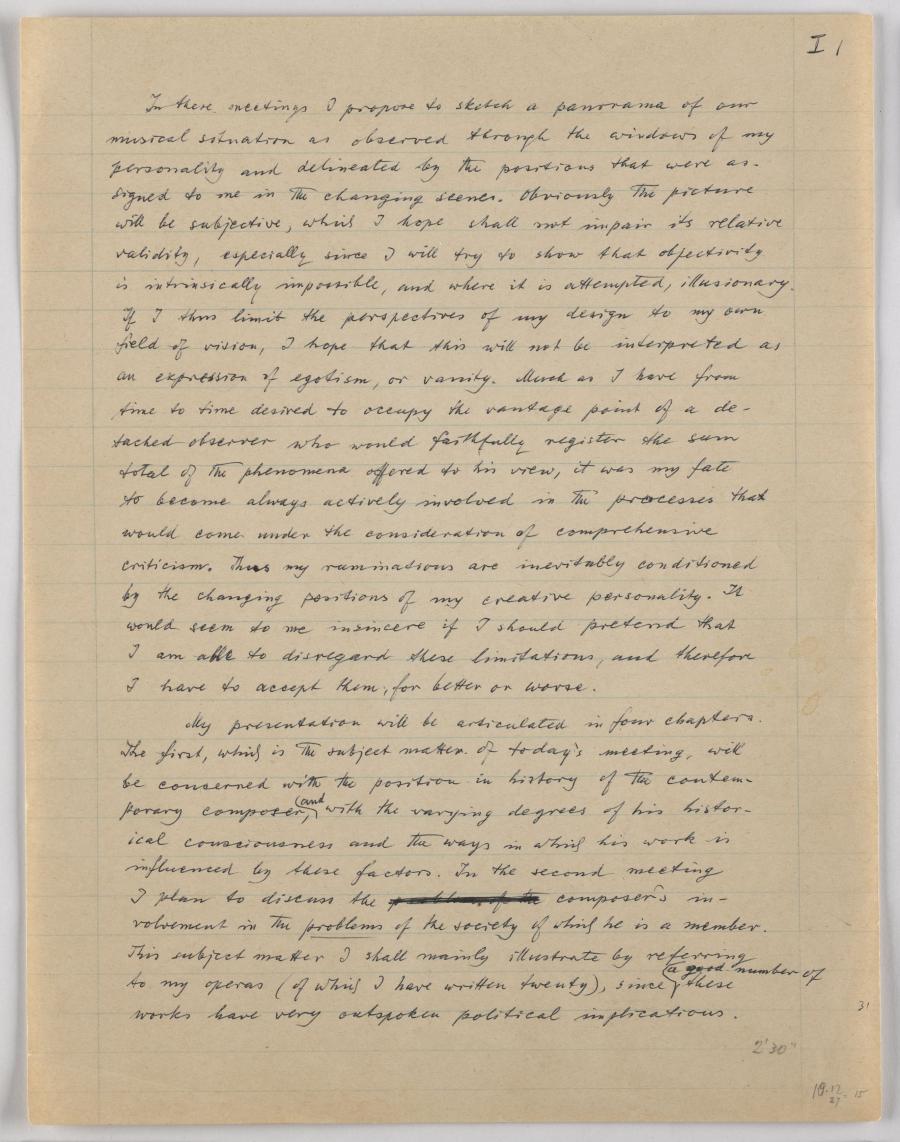

In these meetings I propose to sketch a panorama of our musical situation as observed through the windows of my personality and delineated by the positions that were as- signed to me in the changing scenes. Obviously the picture will be subjective, which I hope shall not impair is relative validity, especially since I will try to show that objectivity is intrinsically impossible, and where it is attempted, illusionary. It I thus limit the perspectives of my design to my own field of vision, I hope that this will not be interpreted as an expression of egotism, or vanity. Much as I have from time to time desired to occupy the vantage point of a de- tached observer who would faithfully register the sum total of the phenomena offered to his view, it was my fate to become always actively involved in the processes that would come under the consideration of comprehensive criticism. This my ruminations are inevitably conditioned by the changing positions of my creative personality. It would seem to me insincere if I should pretend that I am able to disregard these limitations, and therefore I have to accept them for better or worse.

My presentation will be articulated in four chapters.

The first, which is the subject matter of today's meeting, will

be concerned with the position in history of the contem-

porary problems of the society of which he is a member.

This subject matter I shall mainly illustrate by referring

to my operas (of which I have written twenty),

In the third session I should like to talk about the sociological and economic background of the composer's work as it has un- folded in our century. To conclude this series of informal communications I wish to focus the particular situation of composition at the present time, discussing the concept of serialism and investigating how it developed und what became of it. At the end of each session I shall play the tape recording of one of my works, such as would seem appro- priate to illustrate some of the points made.

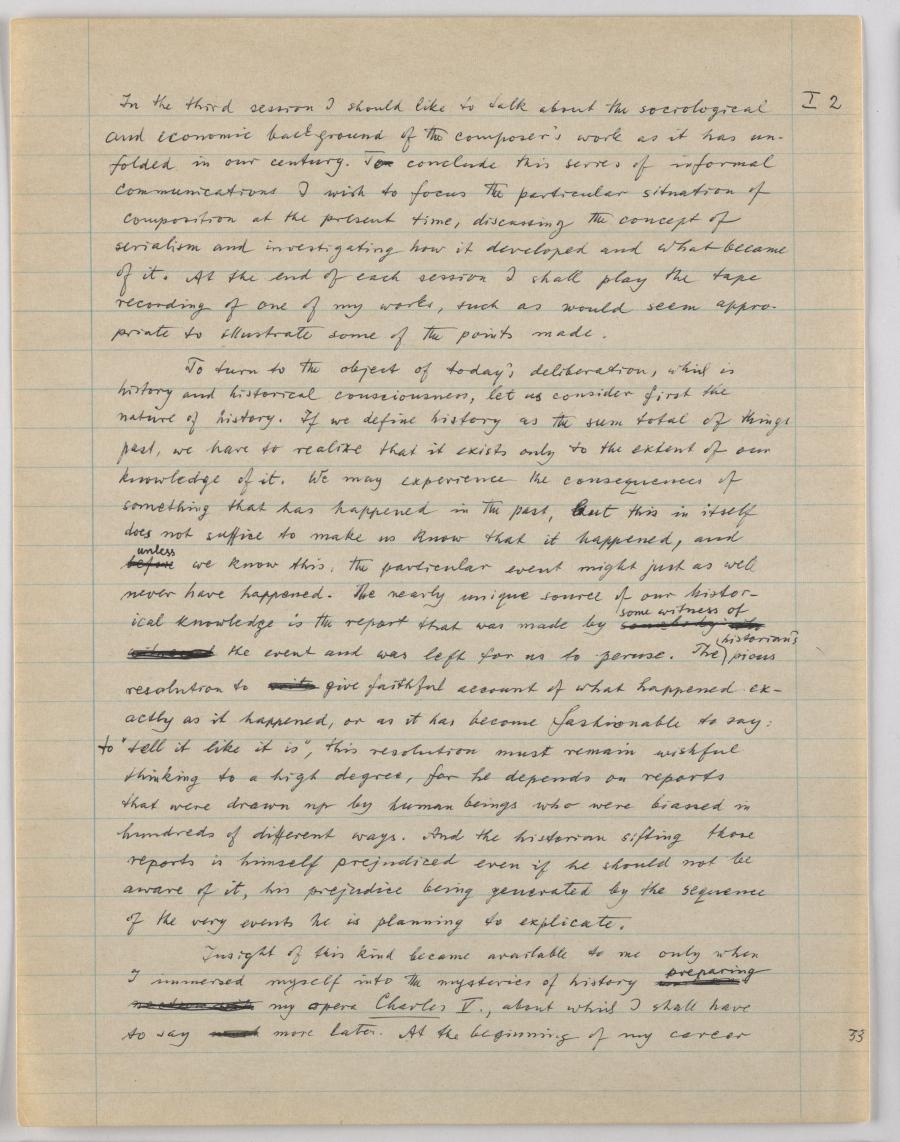

To turn to the object of today's deliberation, which is

history and historical consciousness, let us consider first the

nature of history. It we define history as the sum total of things

past, we have to realize that it exists only to the extent of our

knowledge of it. We may experience the consequences of

something that has happened in the past, but this in itself

does not suffice to make us know that it happened, and

before somebody who

Insight of this kind became available to me only when

I immersed myself into the mysteries of con- Charles V.

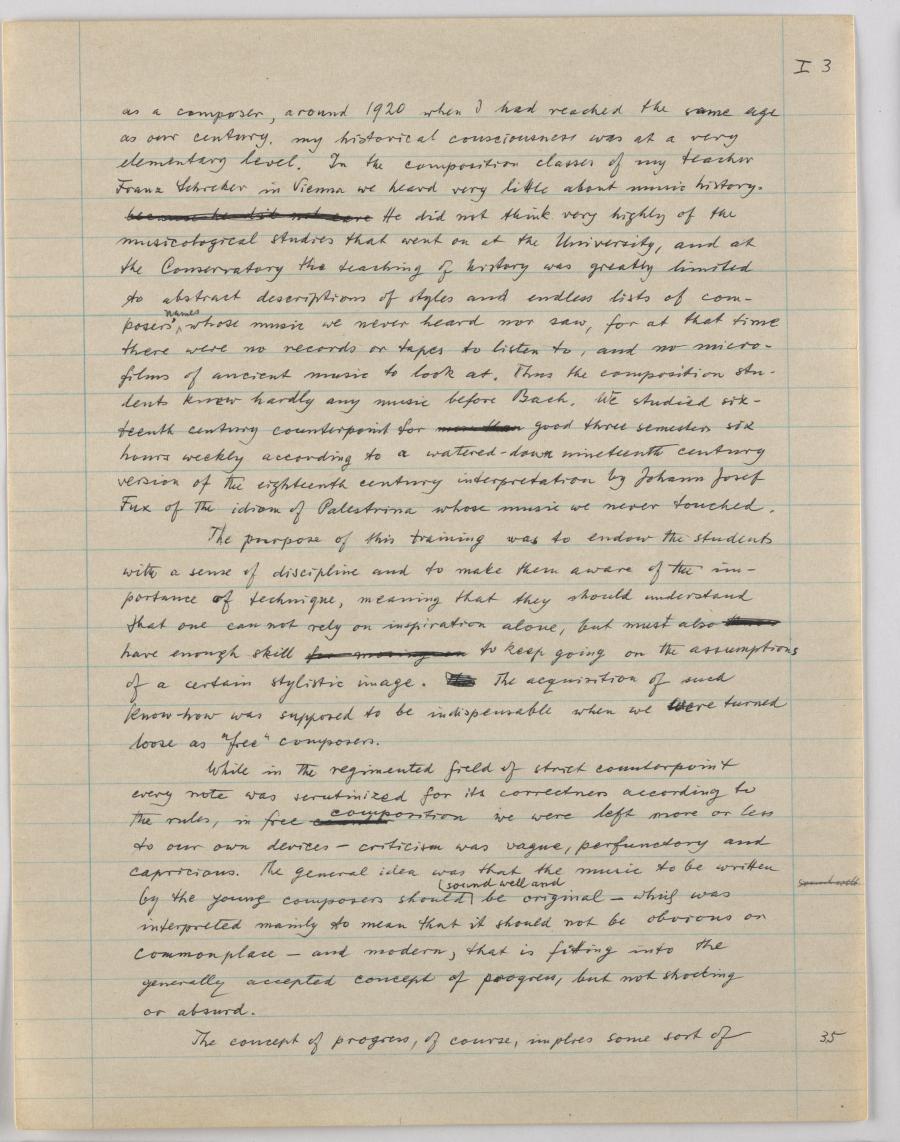

as a composer, around 1920 when I had reached the same age

as our century, my historical consciousness was at a very

elementary level. In the composition classes of my teacher

The purpose of this training was to endow the students

with a sense of discipline and to make them aware of the im-

portance of technique, meaning that they should understand

that one can not rely on inspiration alone, but must also

While in the regimented field of strict counterpoint

every note was scrutinized for its correctness according to

the rules, in counter

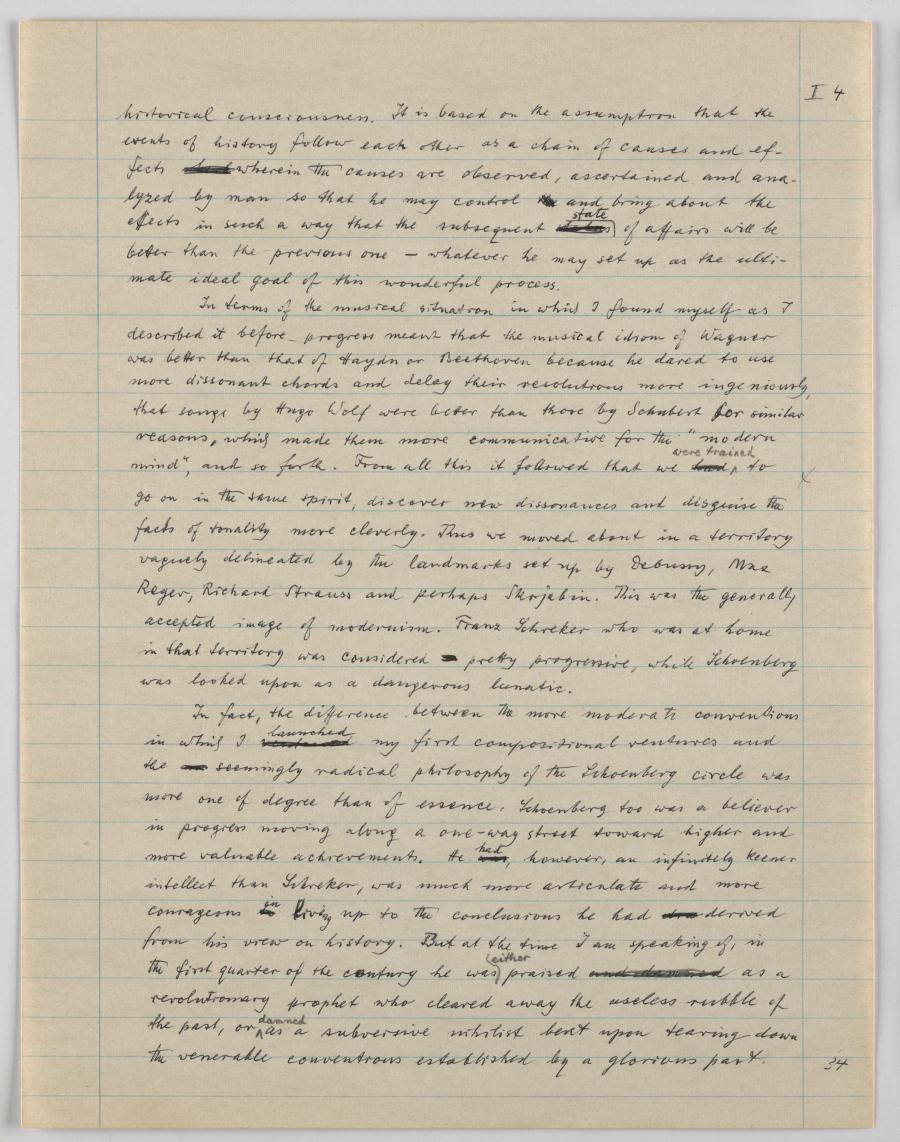

The concept of progress, of course, implies some sort of

historical consciousness. It is based on the assumption that the

events of history follow each other as a chain of causes and ef-

fects

In terms of the musical situation in which I found myself as I

described it before progress meant that the musical idiom of had

In fact, the difference between the more moderate conventions

in which was to

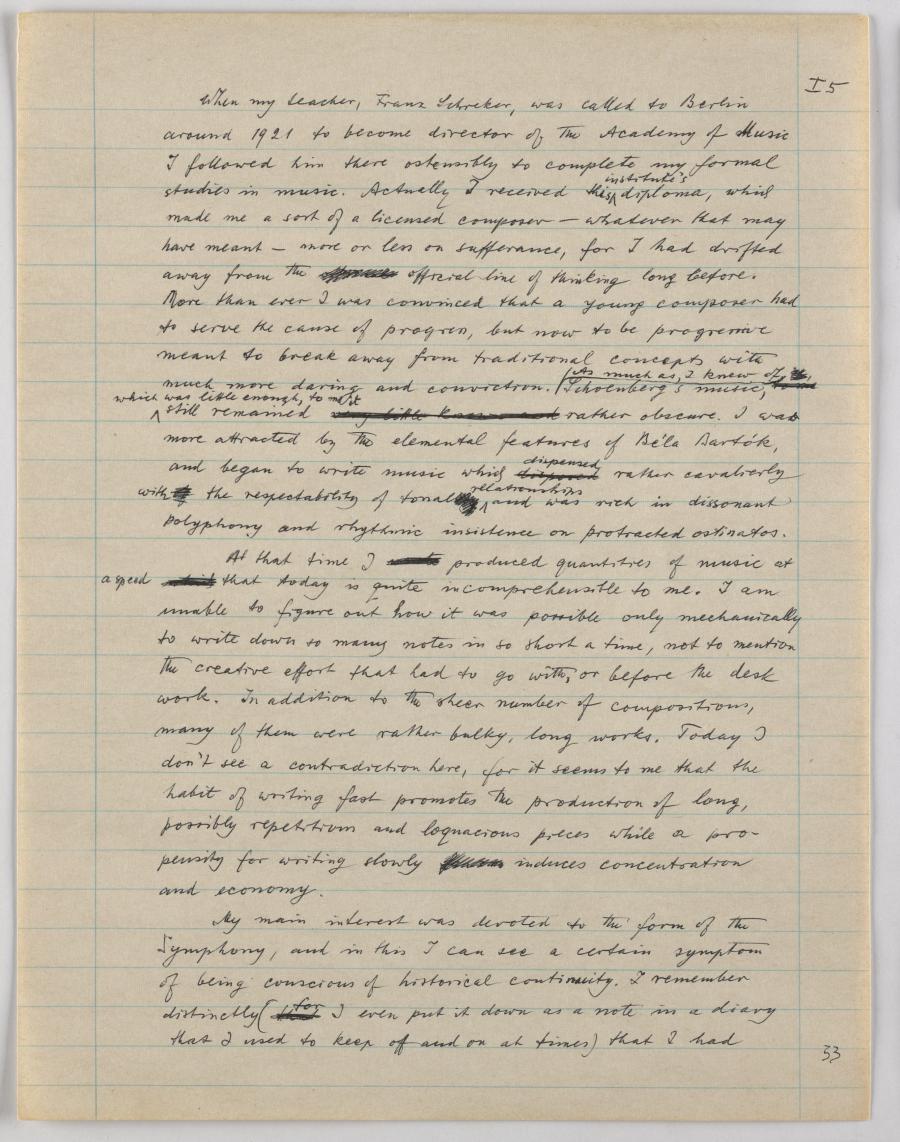

When my teacher, to mevery little known and ratherdisposed

At that time I which that

My main interest was devoted to the form of the

Symphony, and in this I can see a certain symptom

of being conscious of historical continuity. I remember

that

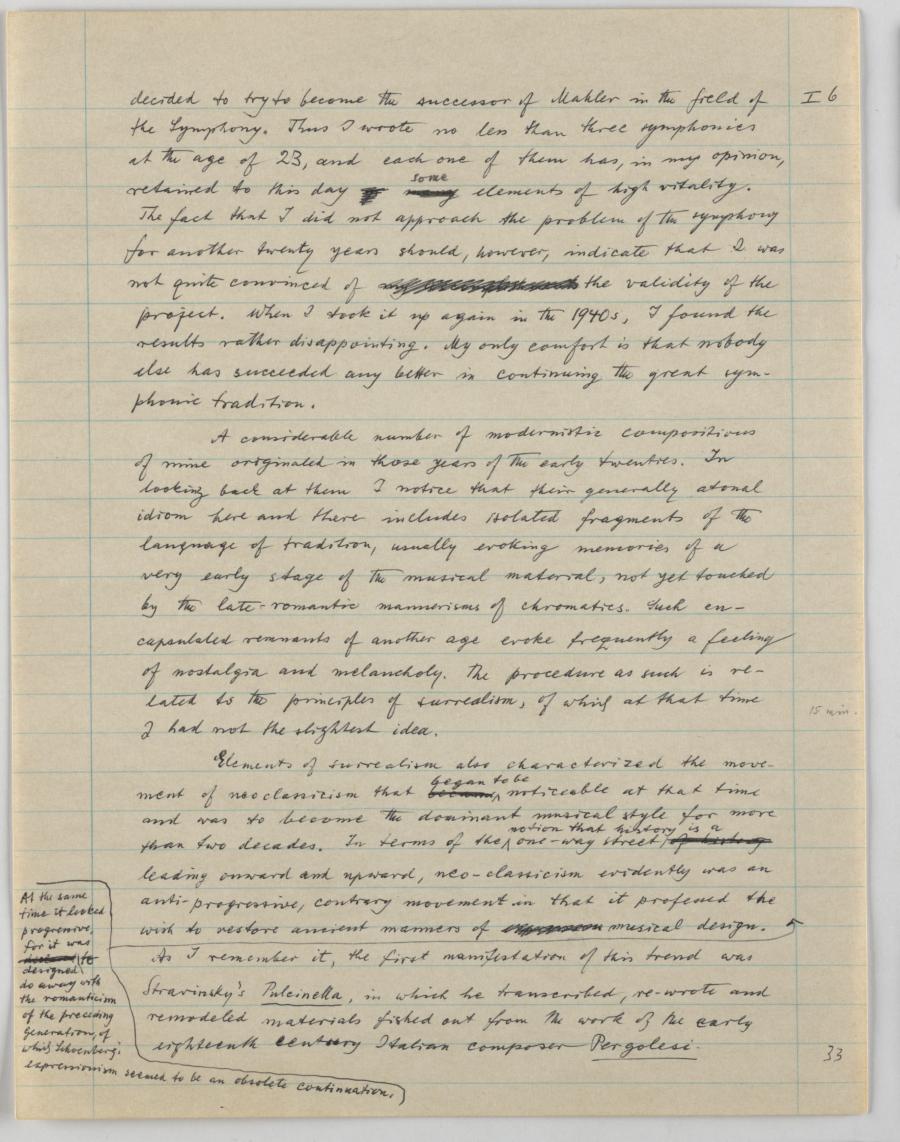

decided to try to become the successor of many

A considerable number of modernistic compositions of mine originated in those years of the early twenties. In looking back at them I notice that their generally atonal idiom here and there includes isolated fragments of the language of tradition, usually evoking memories of a very early stage of the musical material, not yet touched by the late-romantic mannerisms of chromatics. Such en- capsulated remnants of another age evoke frequently a feeling of nostalgia and melancholy. The procedure as such is re- lated to the principles of surrealism, of which at that time I had not the slightest idea.

Elements of surrealism also characterized the move-

ment of neo classicism became of historyexpression musical design. Pulcinella, in which he transcribed, re-wrote and

remodeled materials fished out from the work of the early

eighteenth century Italian composer

.Pergolesi

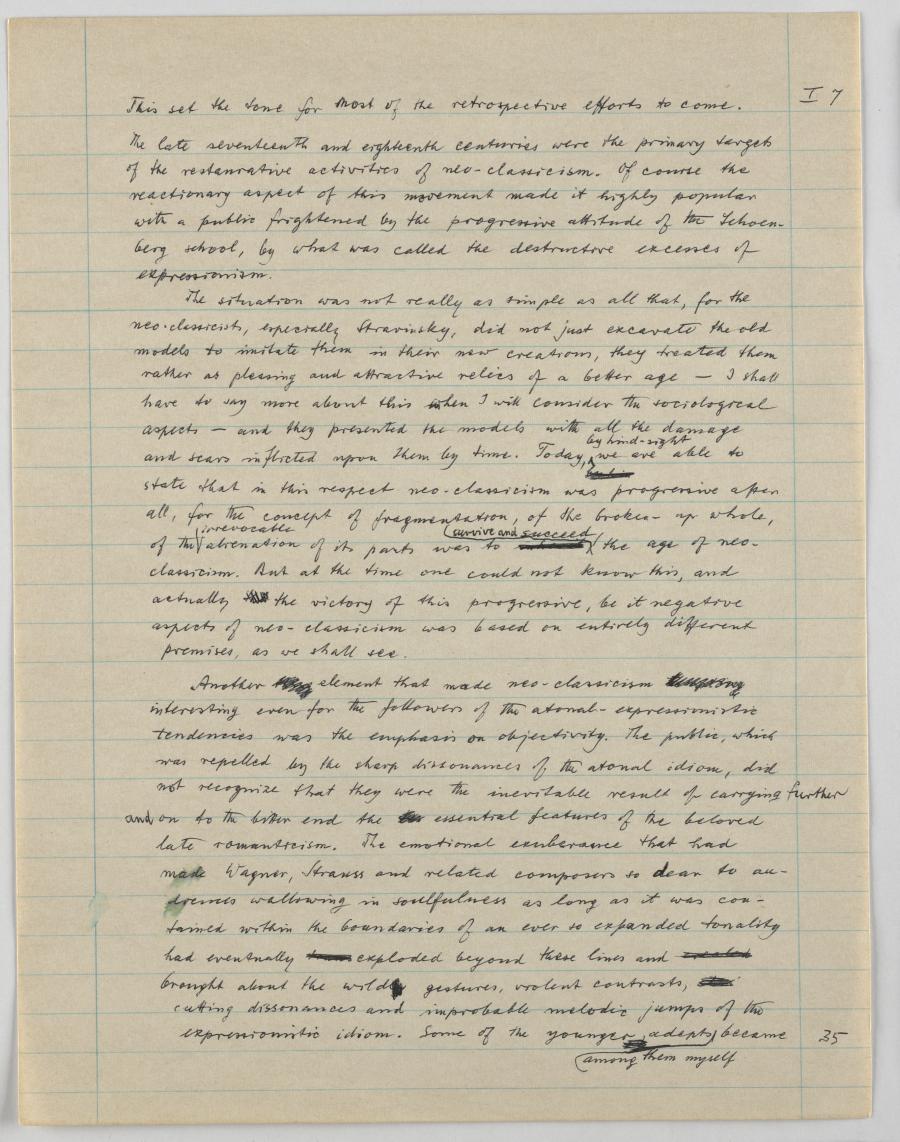

This set the tone for most of the retrospective efforts to come.

The late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were the primary targets

of the restaurative activities of neo-classicism. Of course the

reactionary aspect of this movement made it highly popular

with a public frightened by the progressive attitude of the

The situation was not really as simple as all that, for the

neo-classicists, especially by hininherit

Another ly

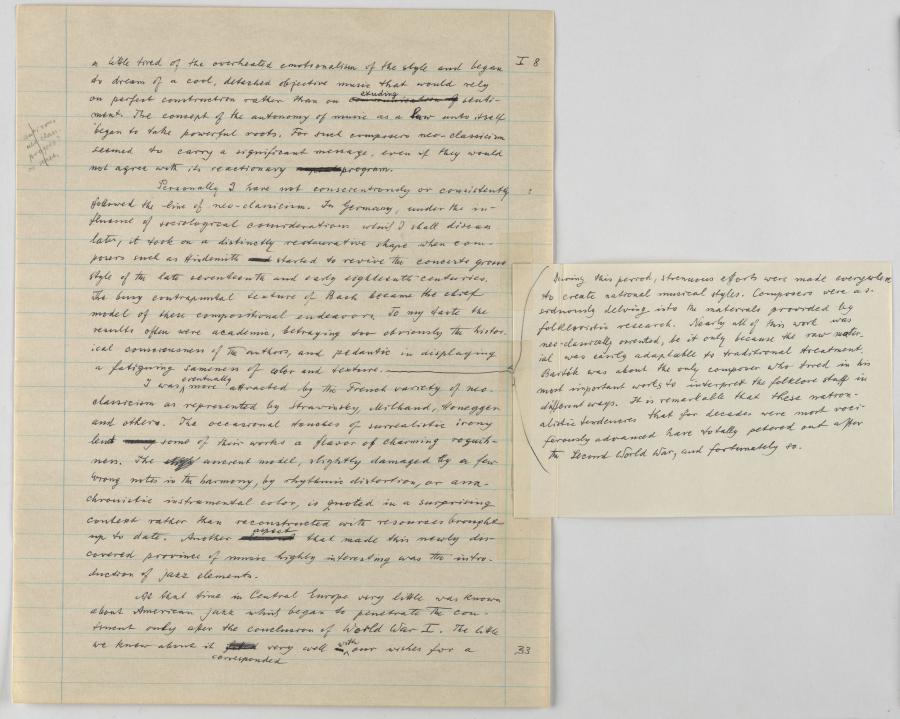

a little tired of the overheated emotionalism of the style and began

to dream of a cool, detached objective music that would rely

on perfect construction rather communication of

Personally I have not conscientiously or consistently

followed the line of neo-classicism. In Germany, under the in-

fluence of sociological considerations which I shall discuss

later, it took on a distinctly restaurative shape when com-

posers such as

I element

At that time in Central Europe very little was known

about American jazz which began to penetrate the con-

tinent only after the conclusion of World War I. The little

we knew about fitted in

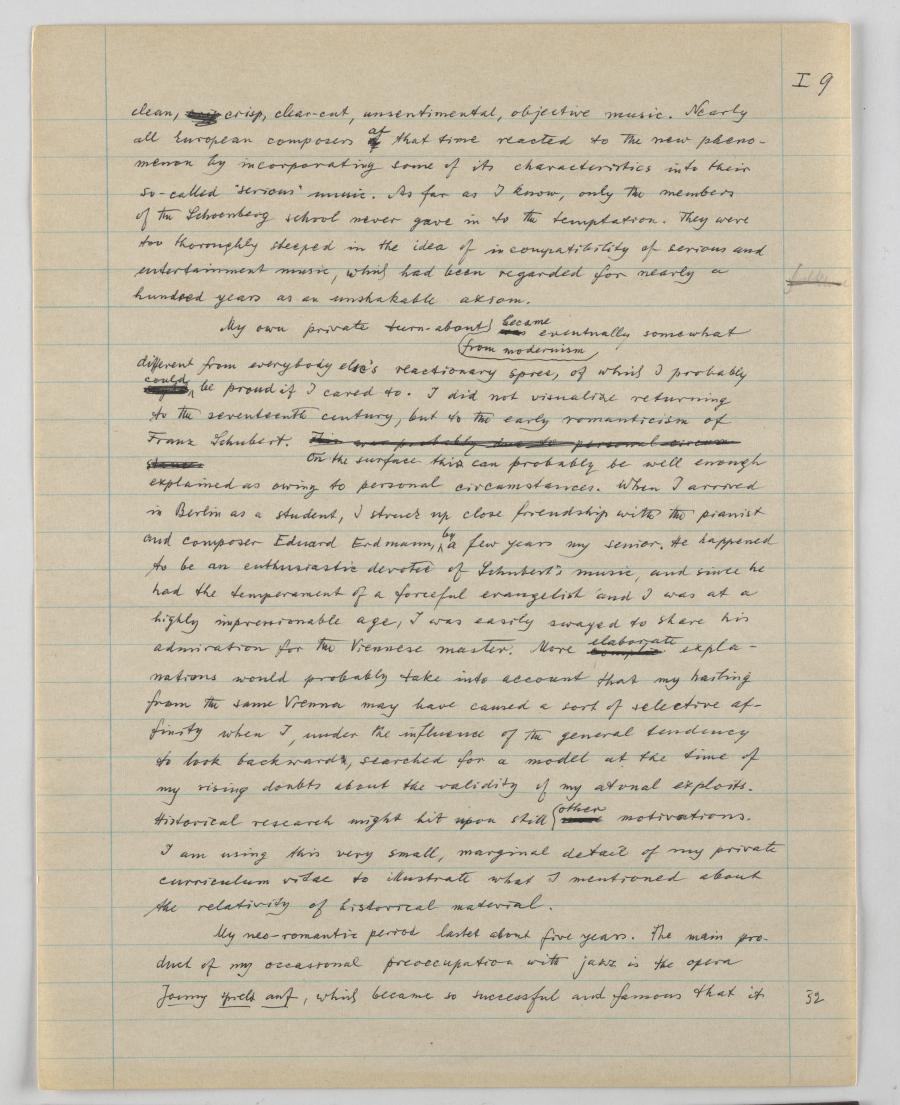

clean, of

My own private was might complic more motivations.

My neo-romantic period lastet about five years. The main pro-

duct of my occasional preoccupation with jazz is the opera

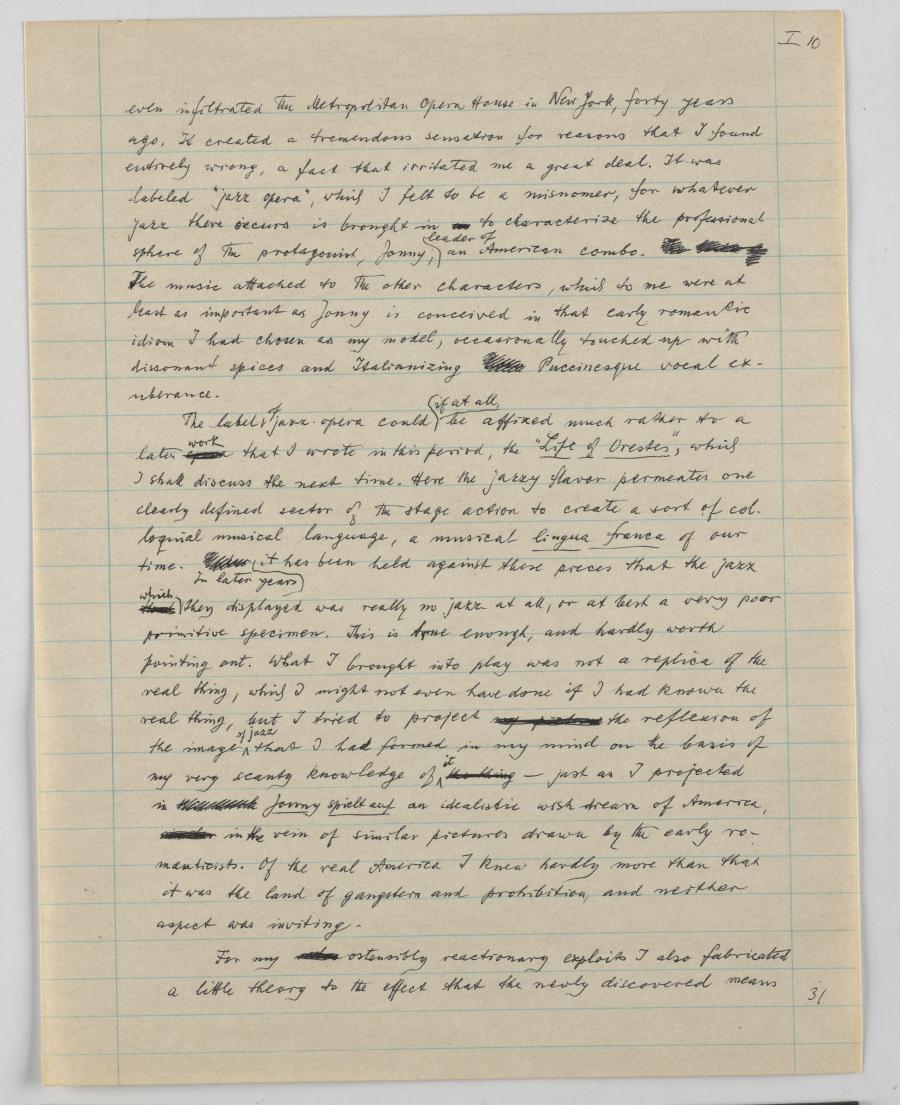

Jonny spielt auf, which became so successful and famous that it

even infiltrated the Metropolitan Opera House in The bulk of

The opera Life of Orestes", which

I shall discuss the next time. Here the jazzy flavor permeates one

clearly defined sector of the stage action to create a sort of col-

loquial musical language, a musical

lingua

francaof our

an idealistic wish dream ofJonny spielt auf

For my

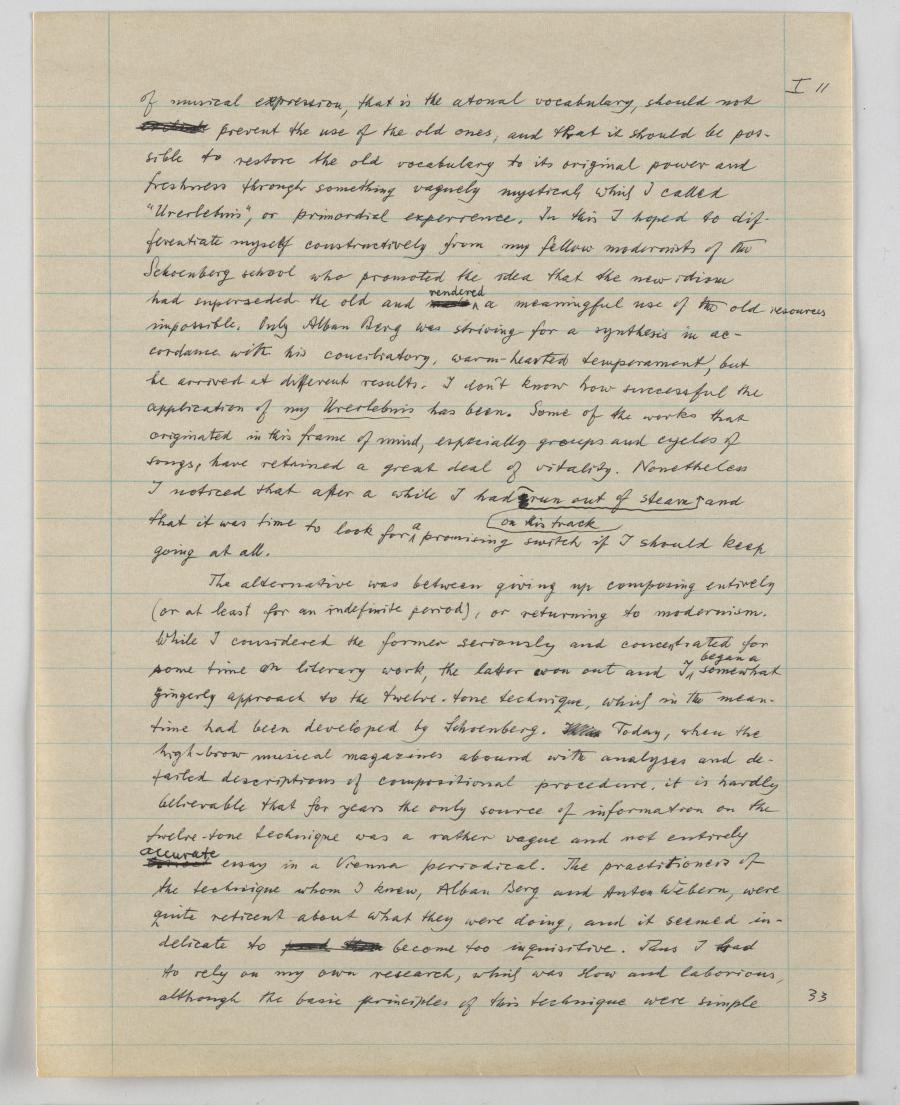

of musical expression, that is the atonal vocabulary, should not

made Urerlebnis has been. Some of the works that

originated in this frame of mind, especially groups and cycles of

songs, have retained a great deal of vitality. Nonetheless

I noticed that after a while I had run out

The alternative was between giving up composing entirely

(or at least for an indefinite period), or returning to modernism.

While I considered the former seriously and concentrated for

some time on literary work, the latter won out correct

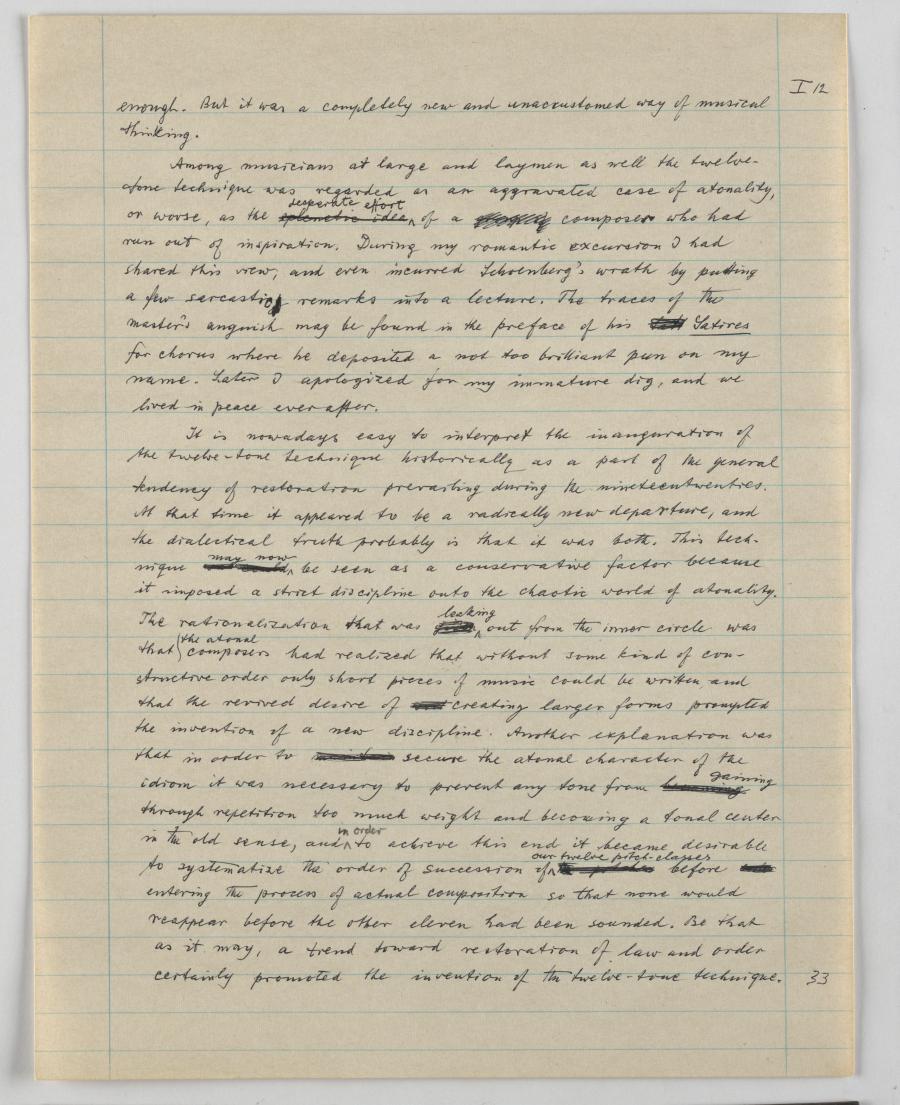

enough. But it was a completely new and unaccustomed way of musical thinking.

Among musicians at large and laymen as well the twelve-

tone technique was regarded as an aggravated case of atonality,

or worse, as splenetic idea group of composerg remarks into a lecture. The traces of the

master's anguish may be found in the preface of his Satires

for chorus where he deposited a not too brilliant pun on my

name. Later I apologized for my immature dig, and we

lived in peace everafter.

It is nowadays easy to interpret the inauguration of

the twelve-tone technique historically as a part of the general

tendency of restoration prevailing during the nineteentwenties.

At that time it appeared to be a radically new departure, and

the dialectical truth probably is that it was both. This tech-

was could given becomming the pitches before

This conjecture is correborated by the they try

Charles V. About its extra-

musical implications I shall talk the next time, which I hope will

make clear that I considered the project one of utmost importance

in every respect. This attitude prompted me to make it also

the point of departure for a completely new phase of my musical

development. After this opera I wrote two works, a set of

Later, when I had come to live in turned out to be of years

It was only in incidentally for

I losked for prototypes I cen-

The tension thus created led to the termination of my

tenure at Vassar College, and I became head of the music depart-

ment at Hamline University in now a to some extent

It has been critized dewoted so much labor to

that seemed to run through the known history of occidental music

and from time to time to

In my teaching I

Today I am not any longer so convinced that this historical

orientation is as necessary or useful as I thought under the

impact of my own historical studies. The nineteenth century

entertained the enviably naive notion that all that had happ-

ened before it was progress theread in the commentary of an

It may be true that strong do

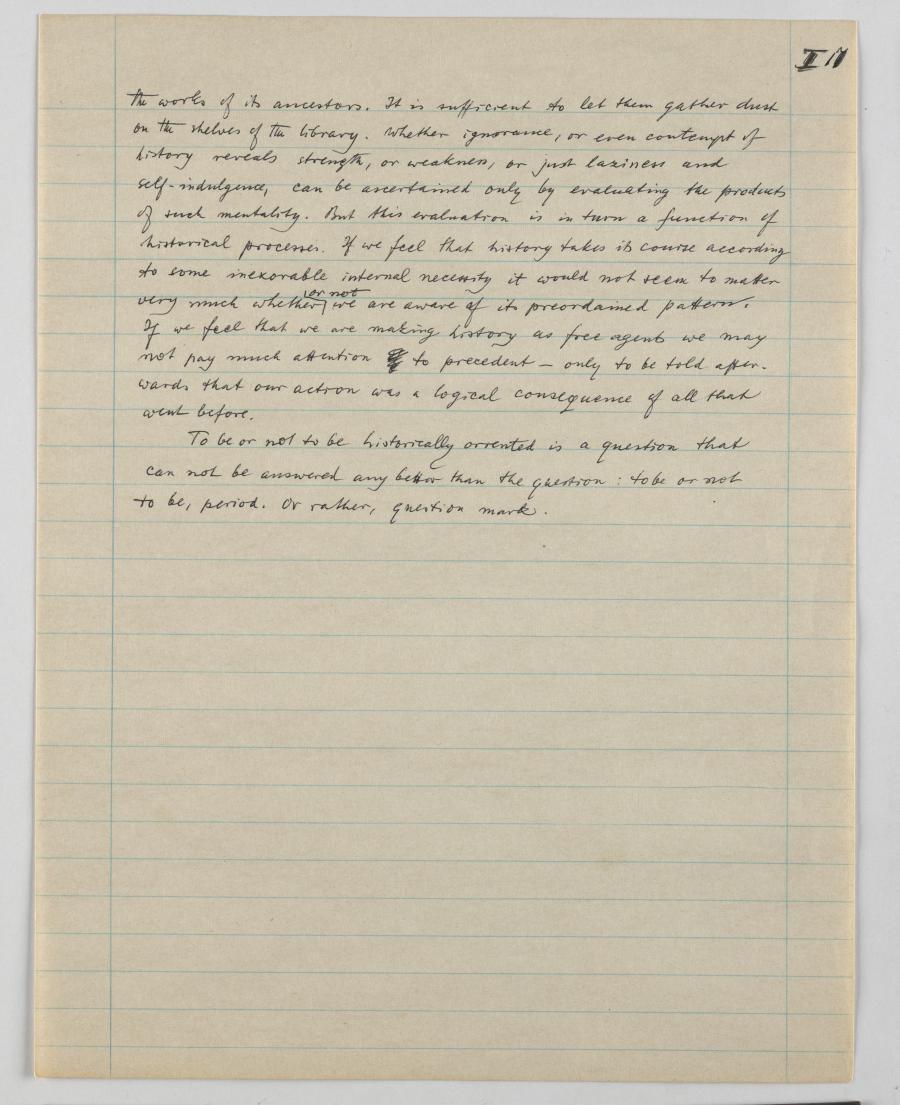

the works of its ancestors. It is sufficient to let them gather dust

on the shelves of the library. Whether ignorance, or even contempt of

history reveals strength, or weakness, or just laziness and

self indulgence, can be ascertained only by evaluating the products

of such mentality. But this evaluation is in turn a function of

historical processes. If we feel that history takes it course according

to some inexorable interal necessity it would not seem to matter

very much

To be or not to be historically oriented is a question that can not be answered any better than the question: to be or not to be, period. Or rather, question mark.