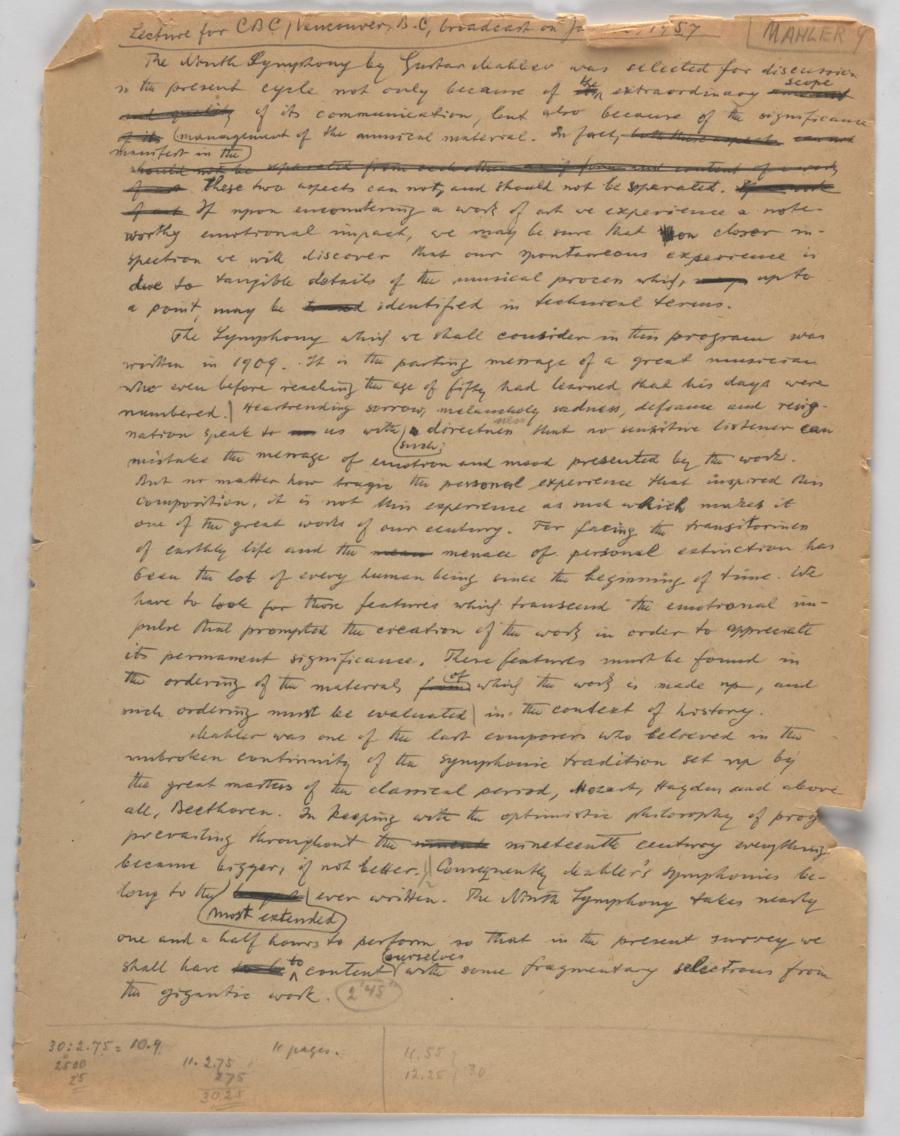

Lecture [about the Ninth Symphony of Gustav Mahler] for CBC, Vancouver, B.C., broadcast on January 20, 1957

Abstract

Für den kanadischen Radiosender CBC analysierte Krenek die 9. Symphonie von Mahler. Der Fokus seiner Analyse liegt dabei auf formalen und strukturellen Merkmalen, auf die komplex verarbeiteten Themen und Motiven und die sich daraus ergebende dramaturgische Dynamik des ausgedehnten Werks.

Um das Radio-Publikum entsprechend auf die Höreindrücke vorzubereiten, illustriert er seine Analyse mit zahlreichen Hörbeispielen.

Lecture for CBC,Vancouver, B.C , broadcast on Ja

MAHLER 9

The its of its on

The Symphony which we shall consider in this program was

written in 1909. It is the parting message of a great musician

who even before reaching the age of fifty had learned that his days were

numbered. Heartrending sorrow, melancholy sadness, defiance und resig-

nation speak to us with a directness from

[ress]

prevailing throughout the to be 2'45"

2'511.2.75 275

30.2511 pages.

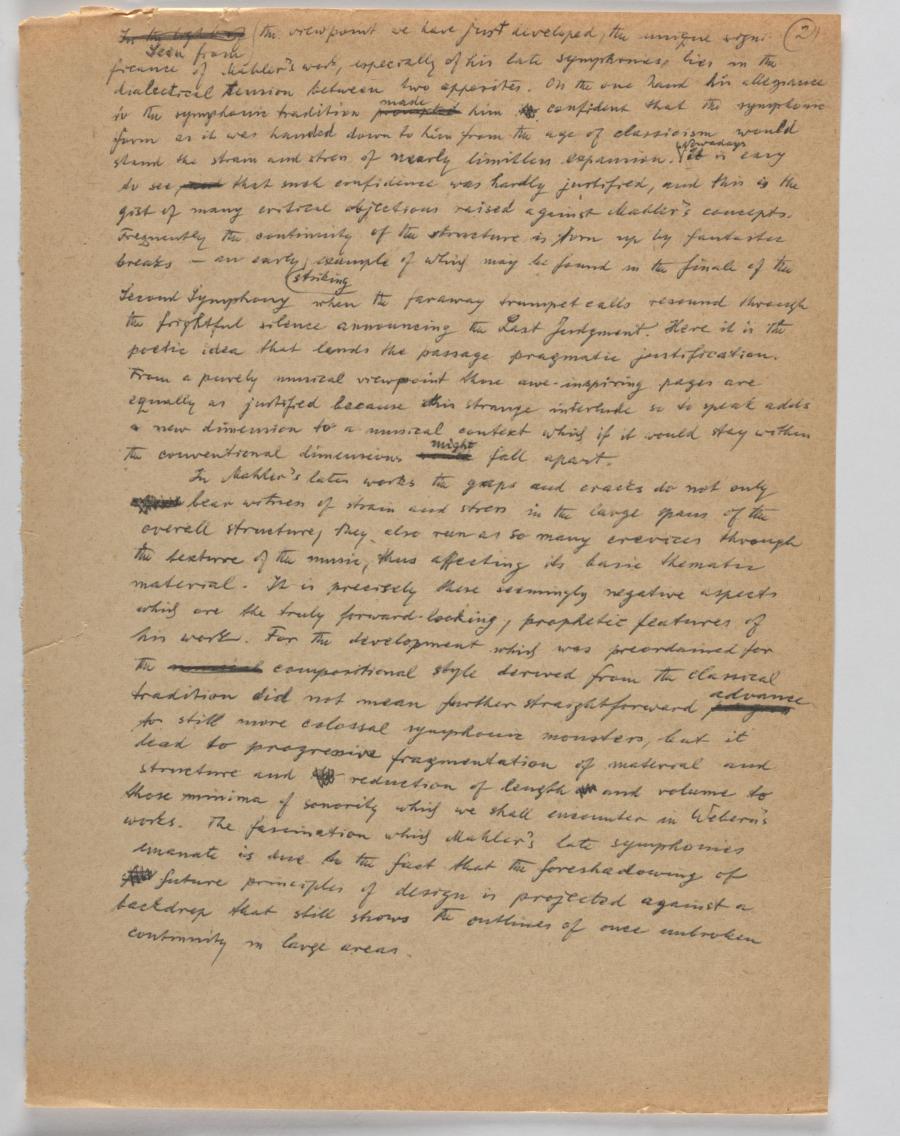

2

In the light of prompted towould

In progress

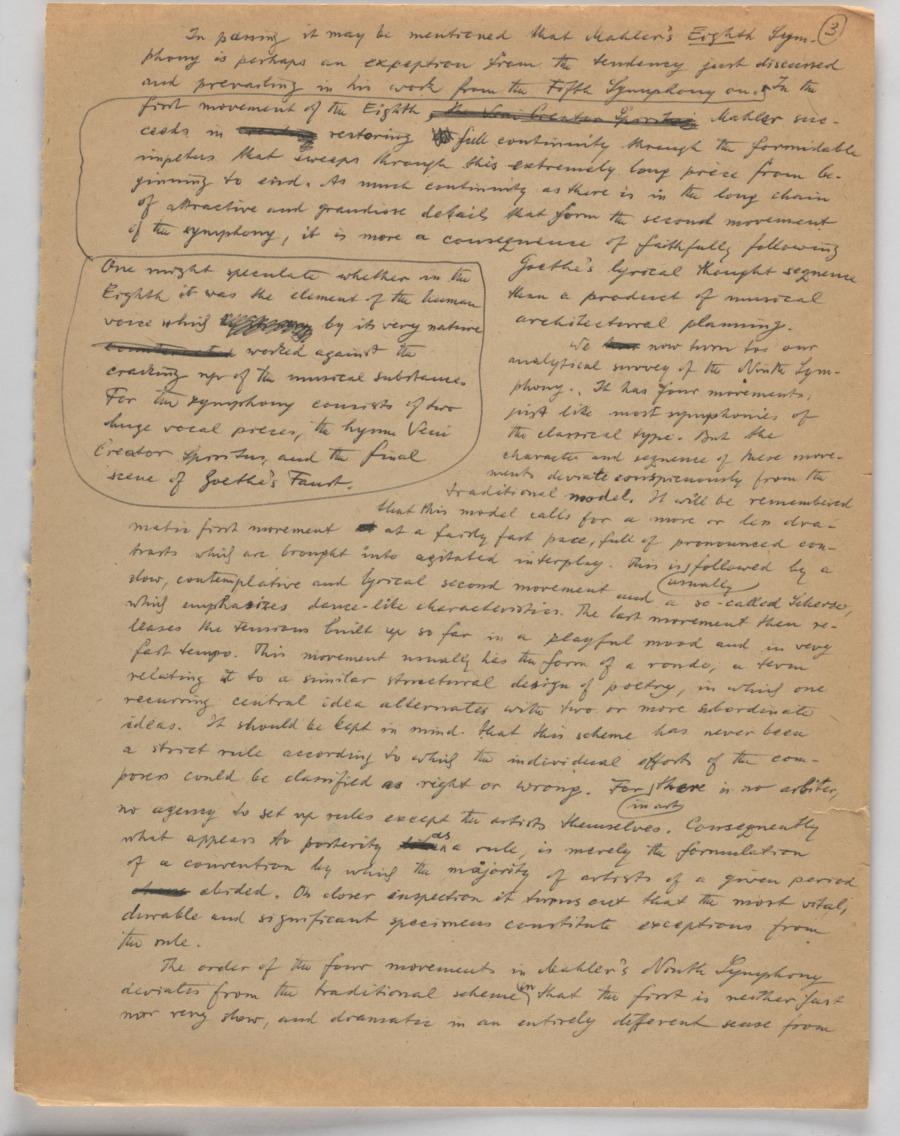

3

In passing it may be mentioned that Eighth Sym-

We like

The order of the four movements in

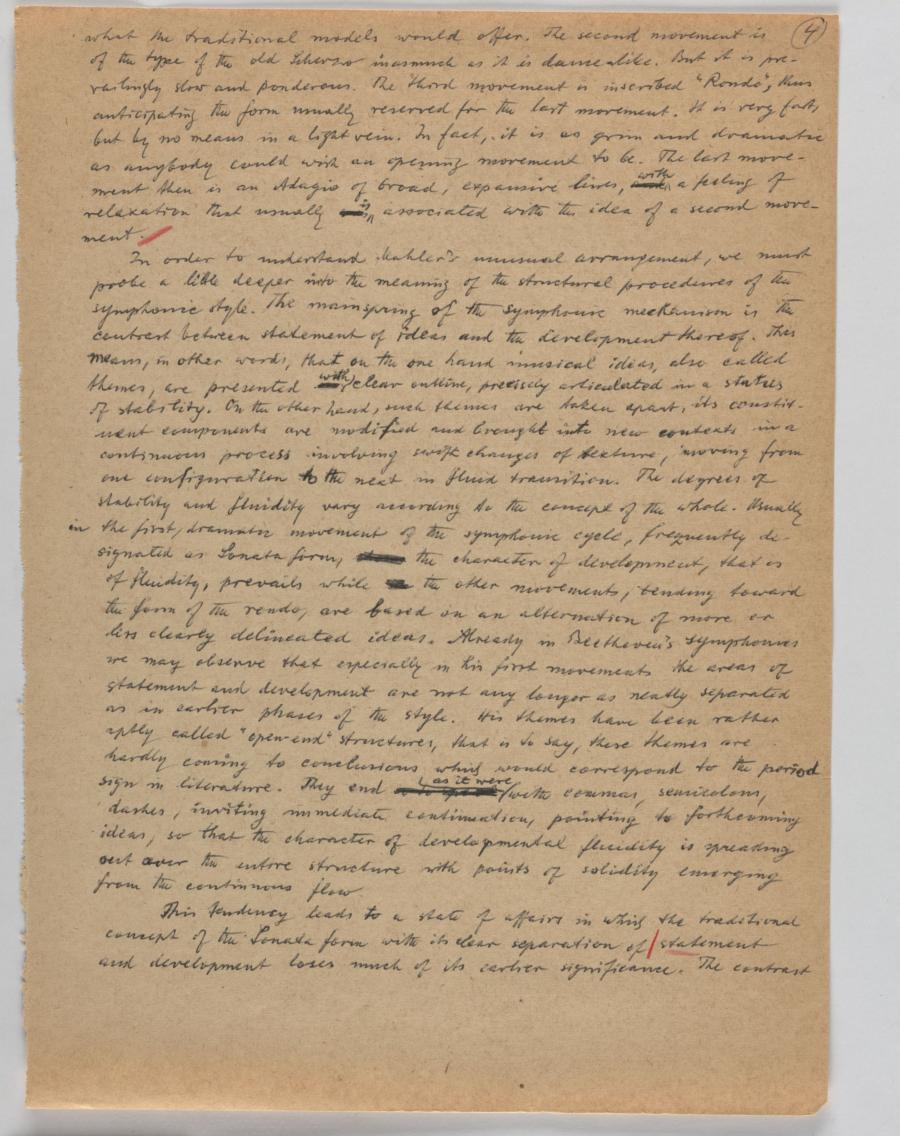

4

what the traditional models would offer. The second movement is

of the type of the old Scherzo inasmuch as it is dance-like. But it is pre-

vailingly slow and ponderous. The third movement is inscribed "Rondo", thus

anticipating the form usually reserved for the last movement. It is very fast,

but by no means in a light vein. In fact, it is as grim and dramatic

as anybody could wish an opening movement to be. The last move-

ment then is an Adagio of broad, expansive and was

In order to understand Mahler's unusual arrangement, we must

probe a litte deeper into the meaning of the structural procedures of the

symphonic style. The mainspring of the symphonic mechanism is the

contrast between statement of ideas and the development thereof. This

means, in other words, that on the one hand musical ideas, also called

themes, are so to speak

This tendency leads to a state of affairs in which the traditional concept of the Sonata form with its clear separation of statement and development loses much of its earlier significance. The contrast

5

of stability and flow is not any longer reserved to this particular form since fluidity becomes increasingly the nature of musical utterance altogether.

It appears that in that

If we call the two basic elements A und B, we find that

the complex A which opens and closes theappears of and the

We shall now hear a few brief examples which should

help us to identify later the context of the entire structure.

The first five bars of the work - obviously part of the complex

which we call A - reveal three

6

phrase which it will be good to remember. Here is the example.

meas. 1-5 (till the middle of the bar)

This is followed by the main substance of our A, a long drawn-out,

simple and haunting melodic line of the Violins, which the listener will

easily identify. I should like to call to his attention the frequent

Turning now to B, we observe in its opening phrase immed-

iately three aspects in which it differs from A. One: a different tonal

flavor (it moves into the minor mode and emphasizes other harmonic

combinations than those of A) Two: the melodic line has Here is themeas. 3 after the b signature - to 3 first beat (p 5)

Toward the end of this first three last bars on p. 7 (3 before return of [Key signature showing F# and C#])

7

1st movement, till 1st bar on p. 20 (4 meas.

before 7, first half of meas.)

We now come in on the analogous situation which concludes the

fourth, enormously extended appearance of B. The high point of the

climax is considerably more powerful than the previous one. The

halting rhythm now takes on the character of catastrophic menace,

thunderously pounded out by the low brass. The composer indicates

a triple forte and adds "mit höchster Gewalt", with supreme force.

The four-tone phrase is again hammered out by kettledrums and

evokes in the ensuing transition the mood of a funeral march. Taken

over by the harps and the solemn, otherworldly sound of chimes, the four-

tone motif imperceptibly becomes the accompaniment of the gentle,

melancholy strains of A. The last reappearance of the passionate

B is suddenly interrupted by one of the strangest details of the symphony.

The musical process seems to disintegrate into inarticulate elements

of sound. A few isolated instruments, far apart from each other, wander

around aimlessly as if lost in the immensity of a suddenly empty

musical space. The fearful mood suggested here evokes, the similar

situation in the finale of the in time and space equally reduced statement

of A.

1st movement, 8th meas. before 15 p. 46 - to end

In a sense the

The ensuing movements elaborate on the commanication set forth by the first, adding forceful emphasis to its various aspects.

8

The second movement is, as mentiond before, dance-like. It is modelled

after the Ländler, the to theas if motion 2nd mot., till last bar on p. 62, first two beats

From the faster moving second section we quote a section of 2nd mot., p. 78, 3rd bar ("a tempo II") to 3rd bar

on p. 79 (first beat)

We shall now hear the third movement in its entirety.

It is the other. Again the phrases are

very short, produces

9

polyphonic, that is the music consist of two or more melodic lines progressing simultaneously, and these lines are so conceived that they constantly rub each other in sharply dissonant combinations. The overall impression is one of extroordinary ferocity.

The second theme of the rondo is somewhat more amiable. Its bouncy, lilting melody grows out of one of the gruff figurations of the first theme, reducing its speed to one half. The attentive listener will notice that the sequence of descending chords underlying this little tune is exactly the same as that which I brought to his attention in the brief, second example from the Ländler movement.

The ferocious first theme repeated Third movement, in its entirety

10

The fourth movement, an extremely slow Adagio, has the char-

acter of an epilogue, stressing the mood of peaceful resignation

which was indicated in the first movement. However the elements of

stuggle and suffering are absent, and thus the expression of resignation

is perhaps less heartrending, but by the same token less original and

different only in texture und harmonic flavor, shall presenting4th mot., beginning till meas. 11, first beat

Coming back for a moment to this little turn I have pointed

out several times, I should like to say that its use is quite

typical of anticipated some of the principles which much later became

identified with surrealism.

At the time when [A]rnold Schoenberg

11

In a sense made