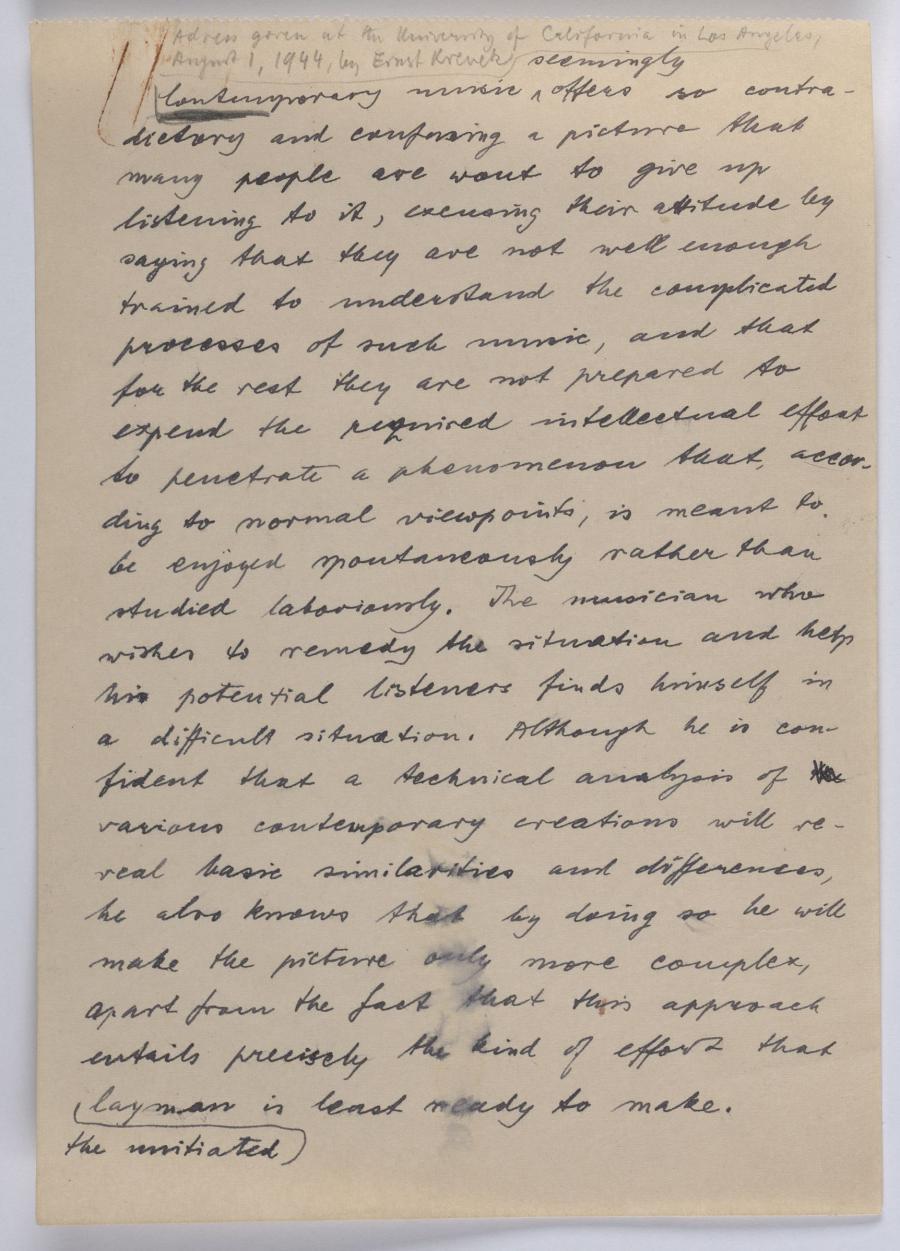

A lecture given at the Los Angeles campus of the University of California on August 1, 1944 by Ernst Krenek

Abstract

Im Sommersemester 1944 hielt Krenek Ansprache an der UCLA. Er setzt sich darin mit dem unterschiedlichen Erfolgen von moderner Musik auseinander. Entlang von Strawinskys auf Ideen von Pierre Souvtchinsky aufbauender Typologisierung von Musik, die entweder „ontologischer“ und psychologischer“ Zeit folgen würde, diskutiert Krenek die Differenzen sowohl auf historisches Repertoire bezogen, als auch für die zeitgenössische Musik, in der die unterschiedlichen Ausrichtungen der Neuen Musik etwas verkürzt mit dem erfolgreichen Werken des Neoklassizismus und den weniger erfolgreichen Zwölftonkompositionen im Gefolge Schönbergs assoziiert werden.

Krenek deklariert sich als Vertreter von Musik der „psychologischen Zeit“ und spielt als Abschluss des Vortrags seine 3. Klaviersonate, op. 92 No. 4.

Contemporary

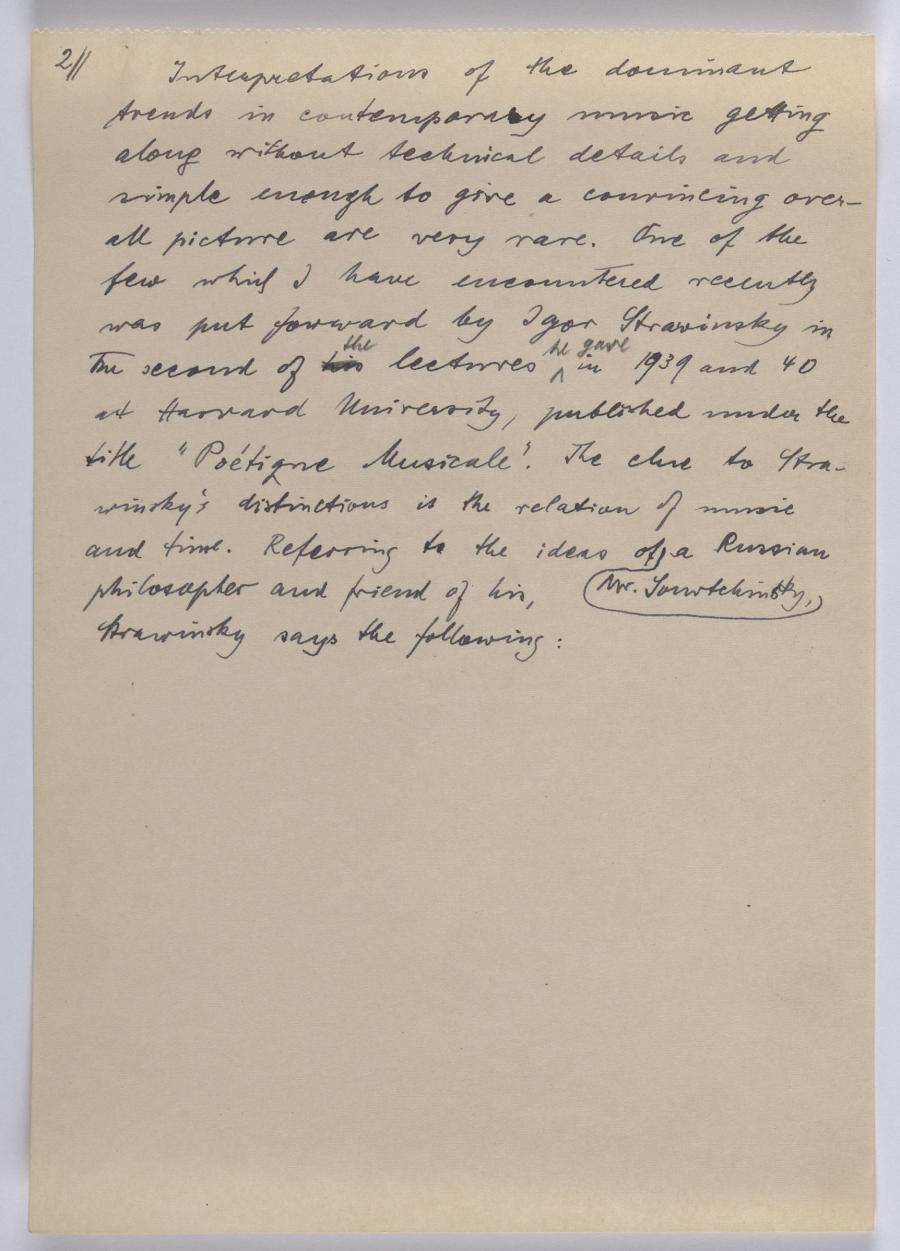

Interpretations of the dominant

trends in contemporary music getting

along without technical details and

simple enough to give a convincing over-

all picture are very rare. One of the

few which I have encountered recently

was put forward by his

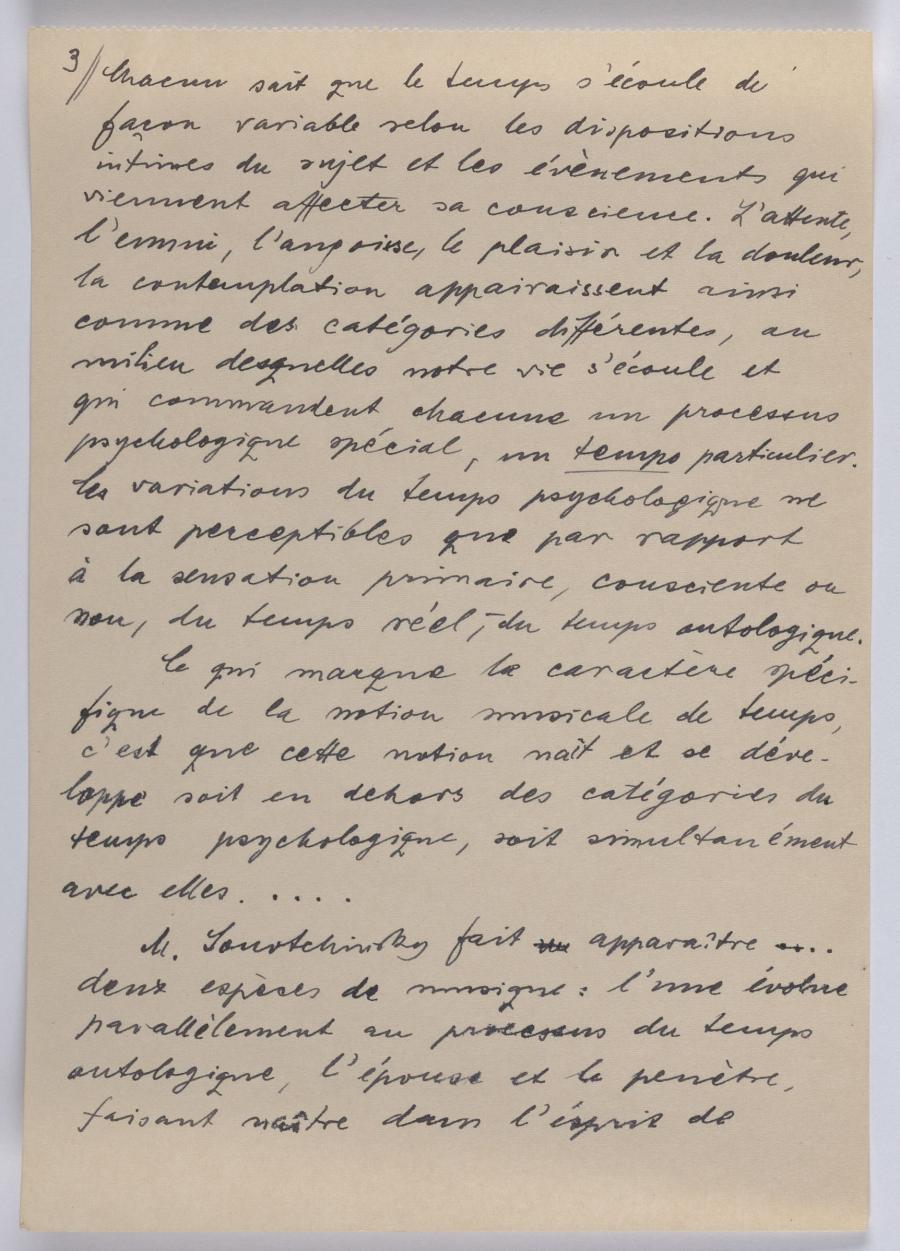

Chacun sait que le temps s’écoule de

façon variable selon les dispositions

intimes du sujet et les évènements qui

viennent affecter sa conscience. L'attente,

l’ennui, l’angoisse, le plaisir et la douleur,

la contemplation appairaissent ainsi

comme des catégories différentes, au

milieu desquelles notre vie s'écoule et

qui commandent chacune un processus

psychologique spécial, un temps particulier.

Les variations du temps psychologique ne

sont perceptibles que par rapport

à la sensation primaire, consciente ou

non, du temps réel, du temps ontologique.

Ce qui marque la caractère spéci- figue de la notion musicale de temps, c'est que cette notion nait et se déve- loppe soit en dehors des catégories du temps psychologique, soit simultanément avec elles.....

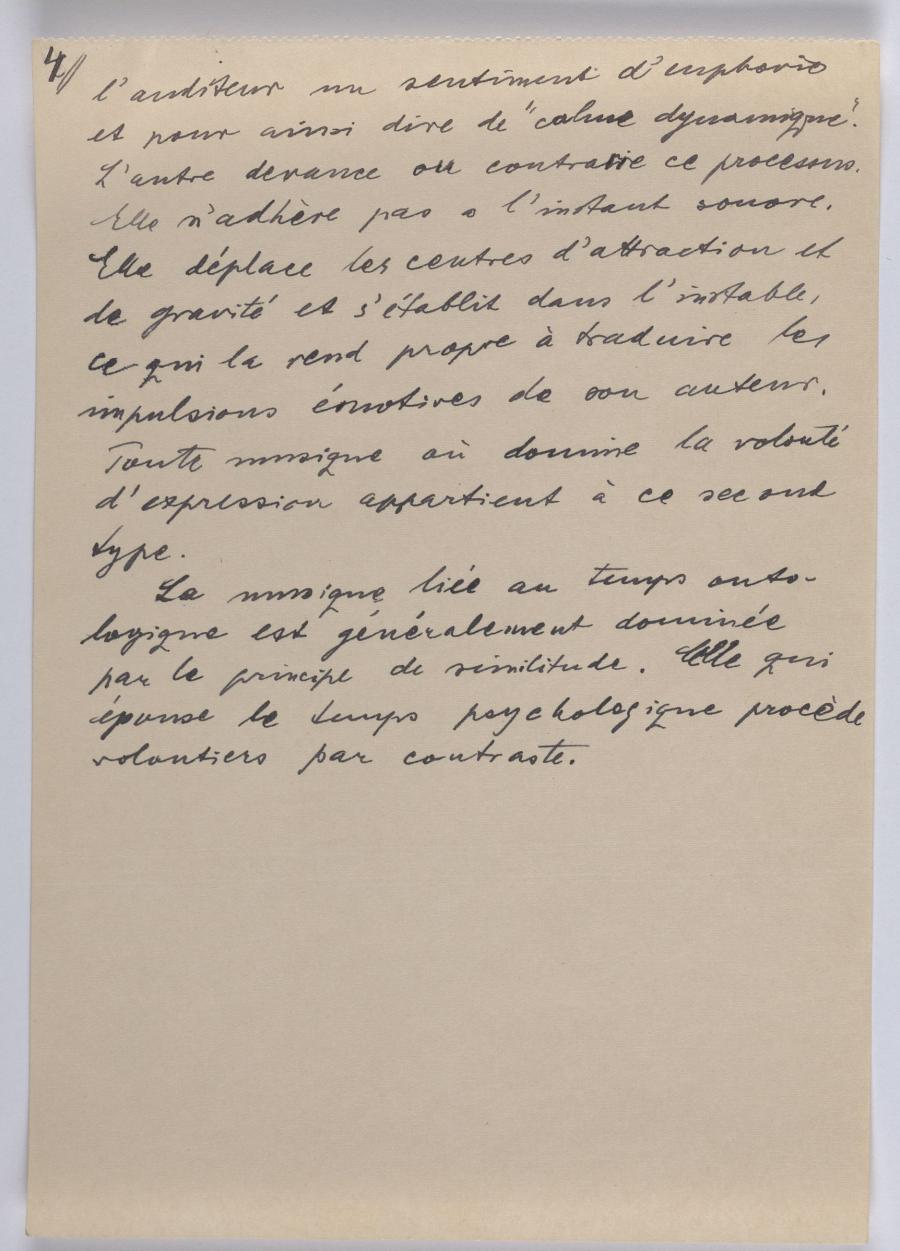

l’auditeur un sentiment d’euphorie et pour ainsi dire de "calme dynamique". L’autre devance ou contrarie ce processus. Elle n'adhère pas à l'instant souvre Elle déplace les centre sd'attraction et de gravité et s'établit dans l'instable, ce qui la rend propre à traduire les impulsions émotives de son auteur. Toute musique où domine la volonté d'expression appartient à ce second type.

La musique licé au temps onto- logique est généralement dominée par le principe de similitude. Elle qui épouse le temps psychologique procède volontiers par contraste.

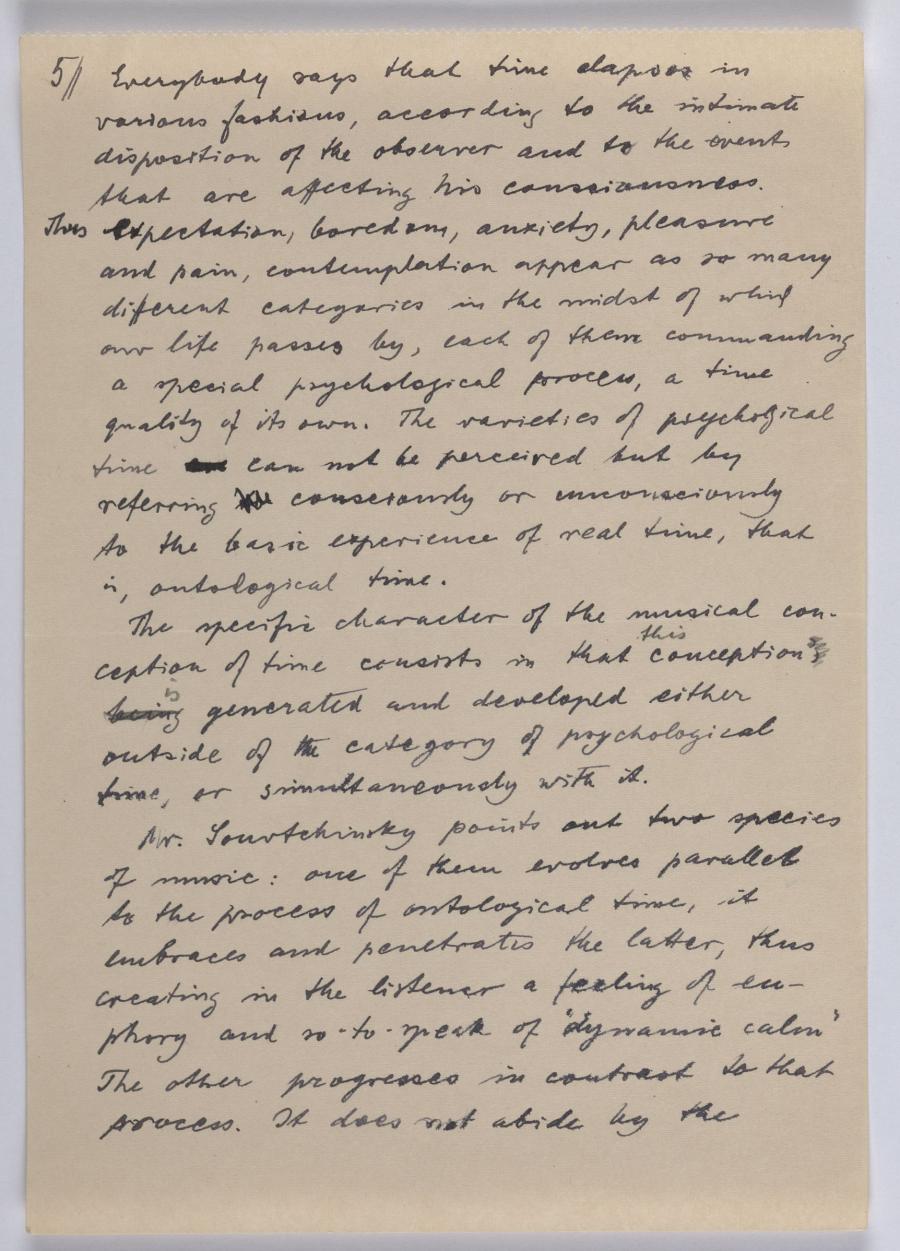

5//

Everybody says that time elapses in

various fashions, according to the intimate

disposition of the observer and to the events

that are effecting his consciousness.

The specific character of the musical con-

ception of time consists in 'sbeing

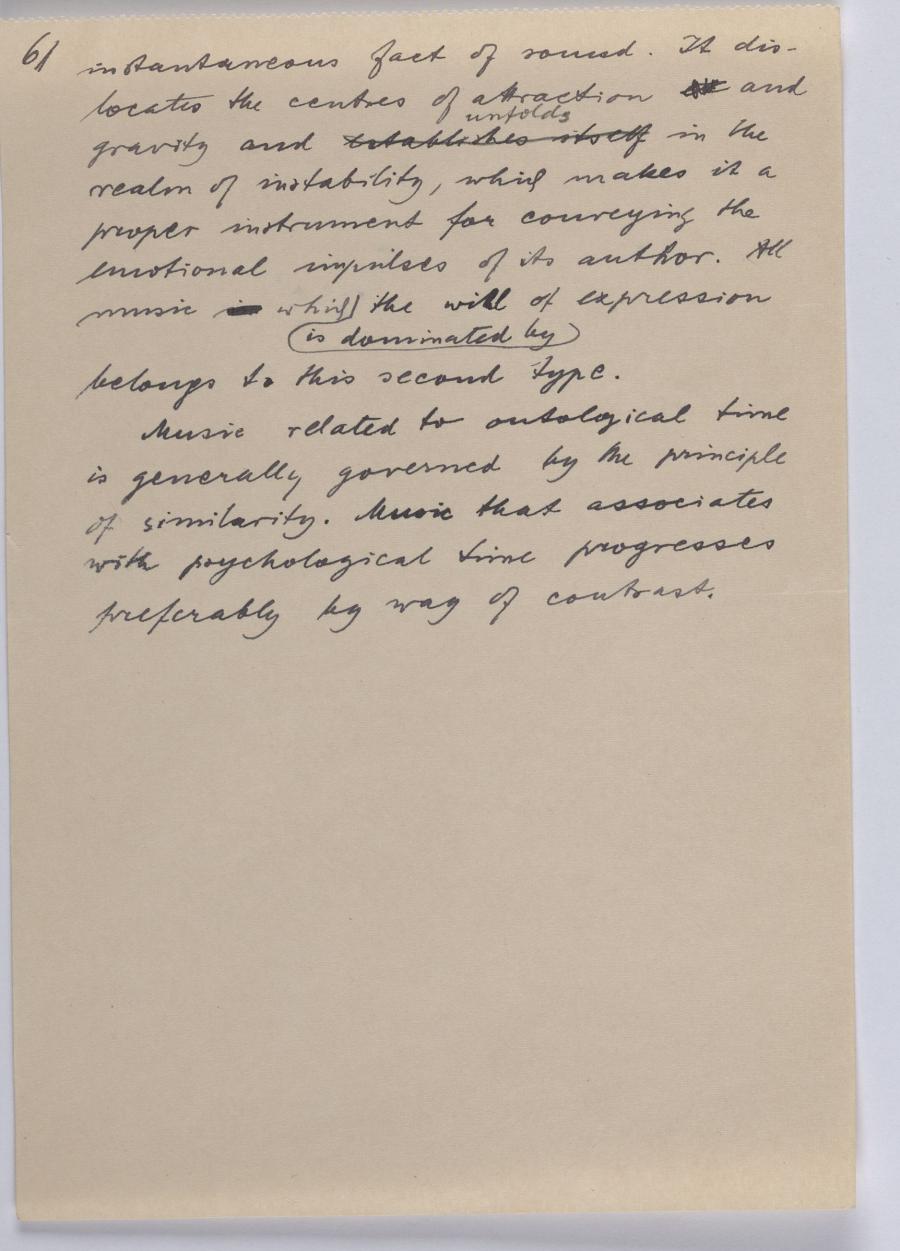

instantanous fact of sound. It dis-

locates the centres of attraction establishes itself in which

Music related to ontological time is generally governed by the principle of similarity. Music that associates with prochological time progresses preferably by way of contrast.

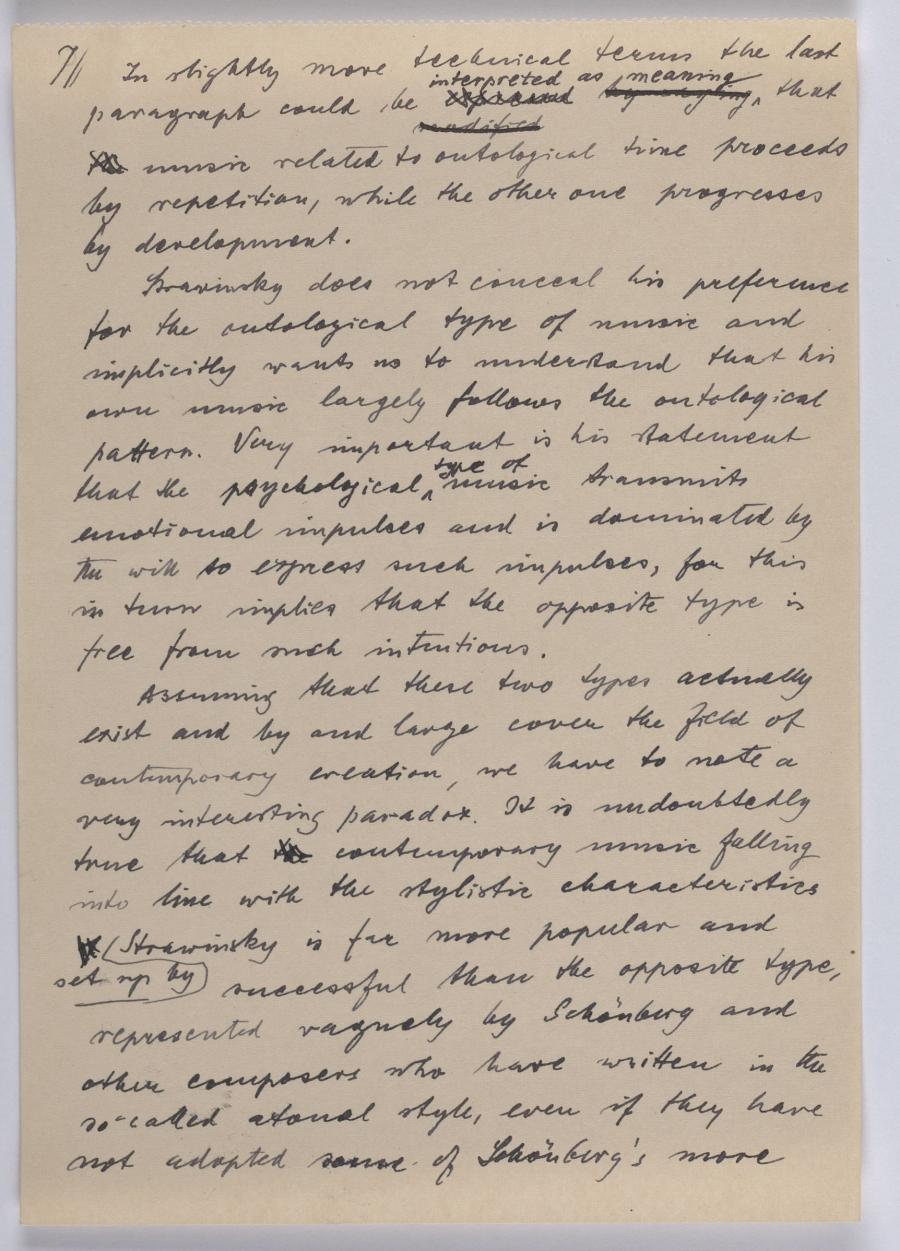

7//

In slightly more technical terms the last

paragraph expressed by modified

Assuming that these two types actually

exist and by and large cover the field of

contemporary creation, we have to note a

very interesting paradox. It is undoubtedly

true that of

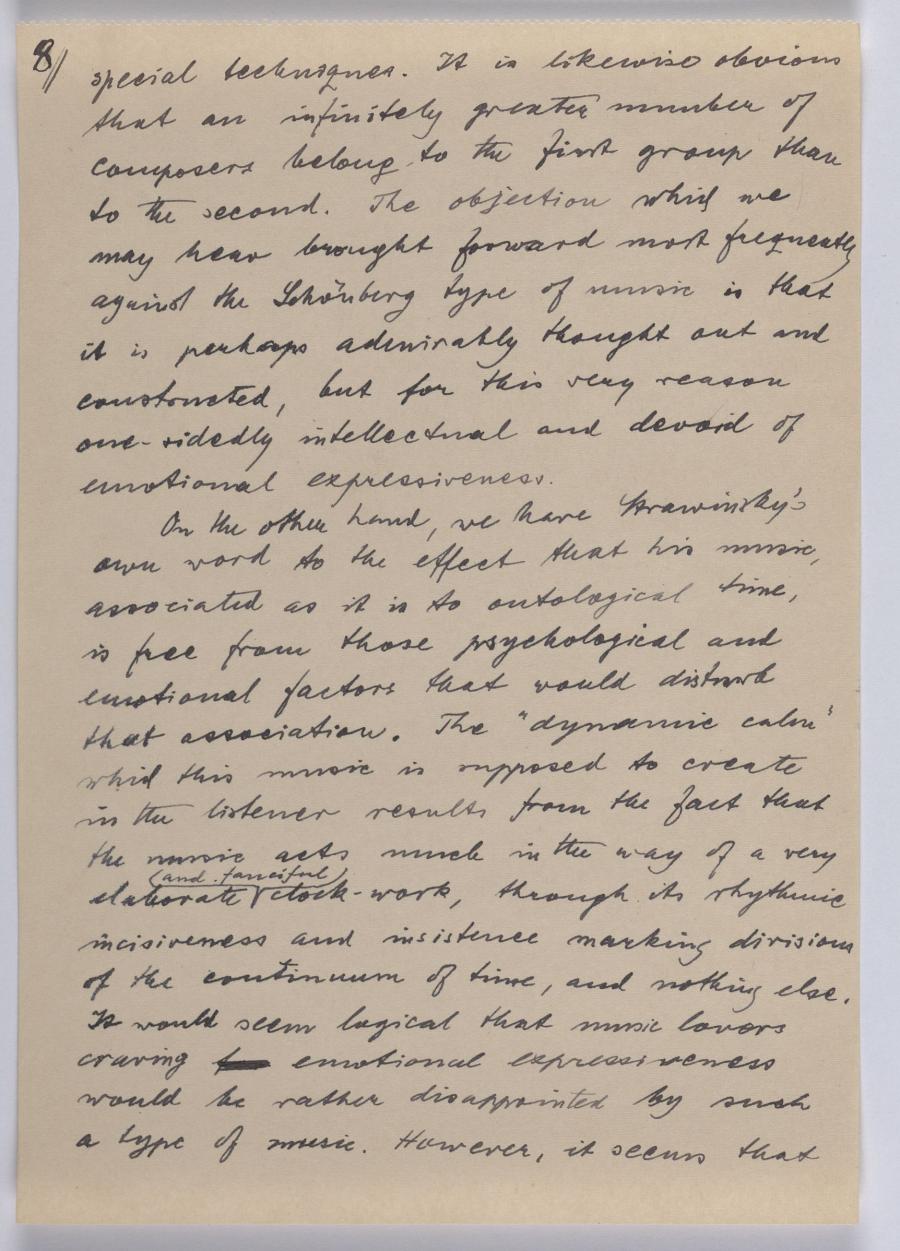

special techniques. It is likewise obvious

that an infinitely greater number of

composers belong to the first group than

to the second. The objection which we

may hear brought forward most frequently

against the

On the other hand, we have

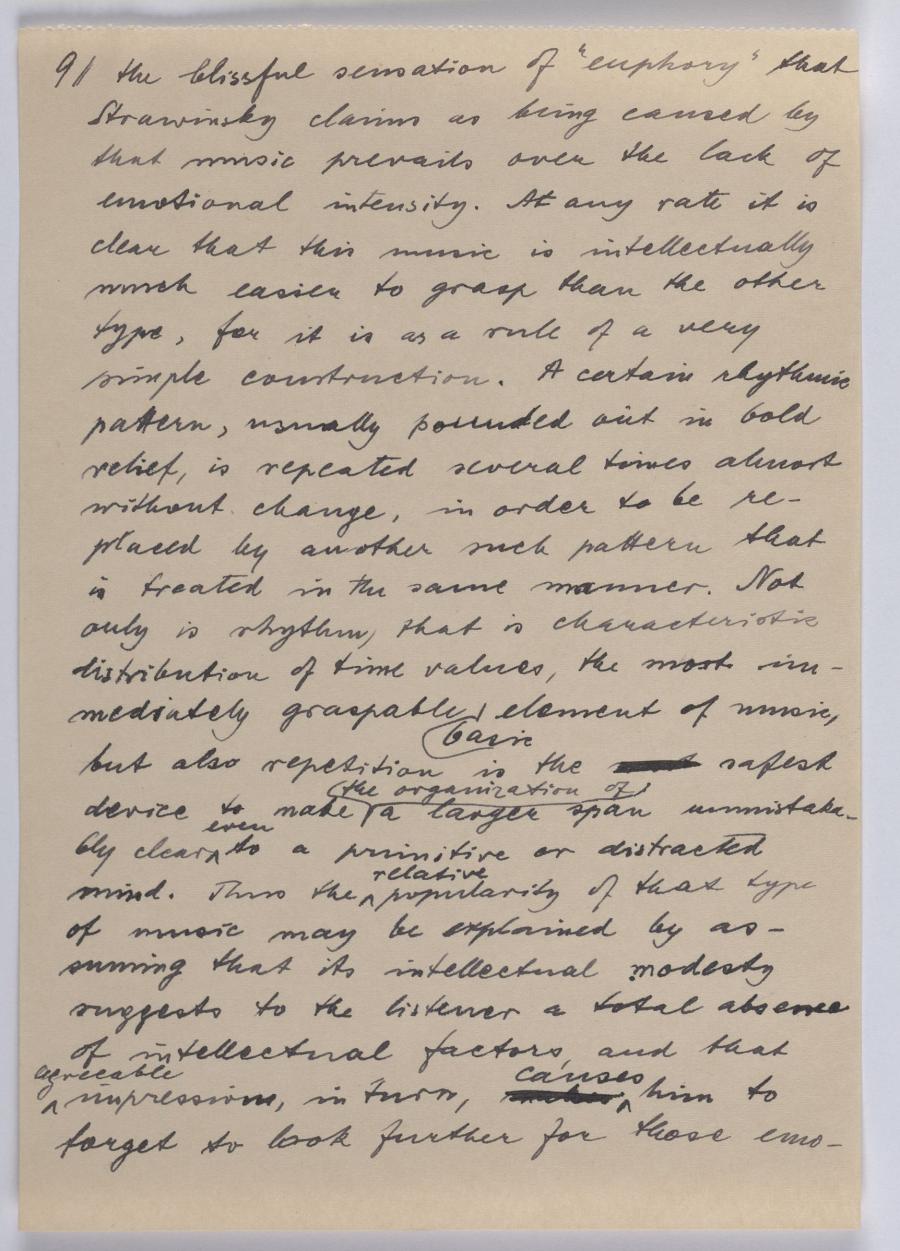

the blissful sensation of "euphory" that

makes

tional factors in which he had pro- fessed so strong an interest.

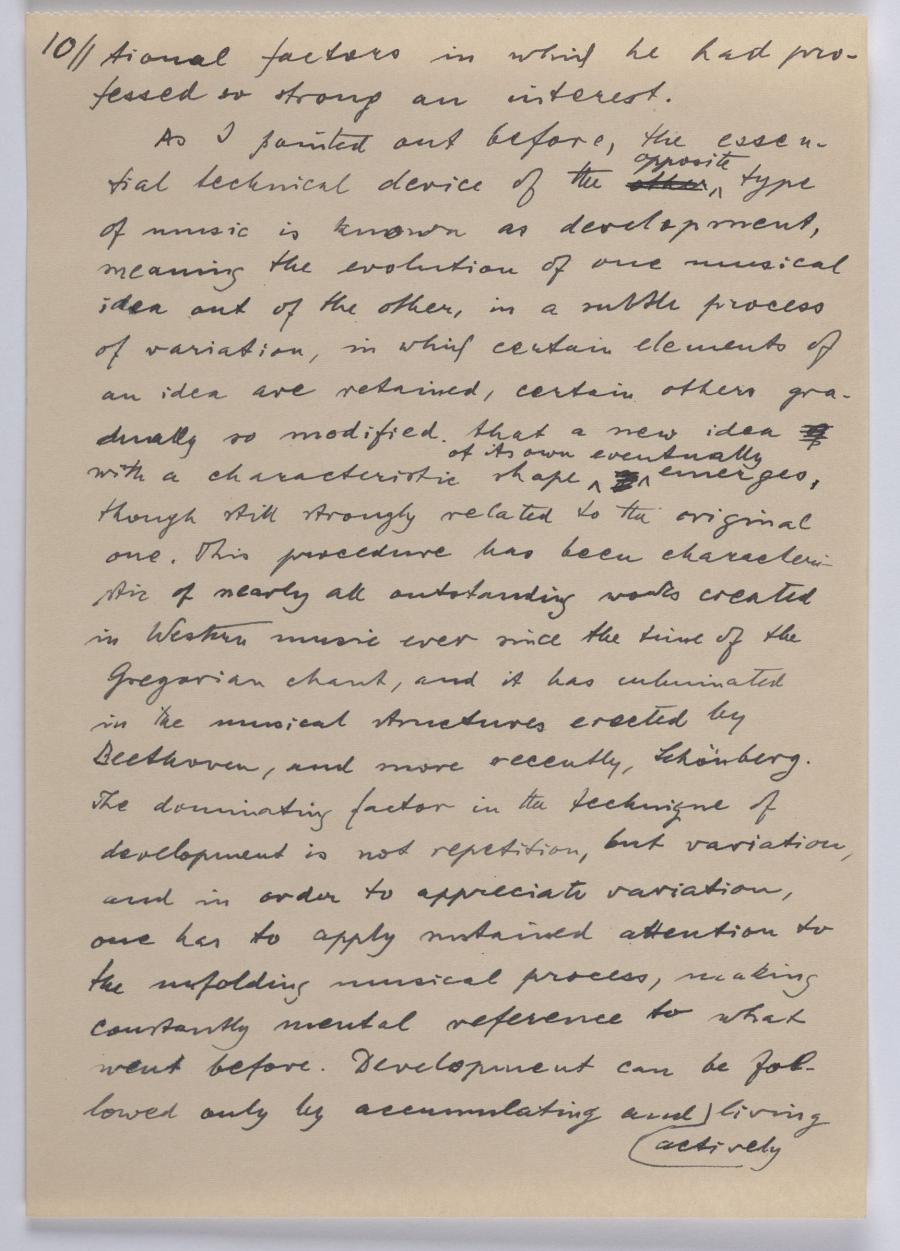

As I pointed out before, the essen-

tial technical device other emerges,

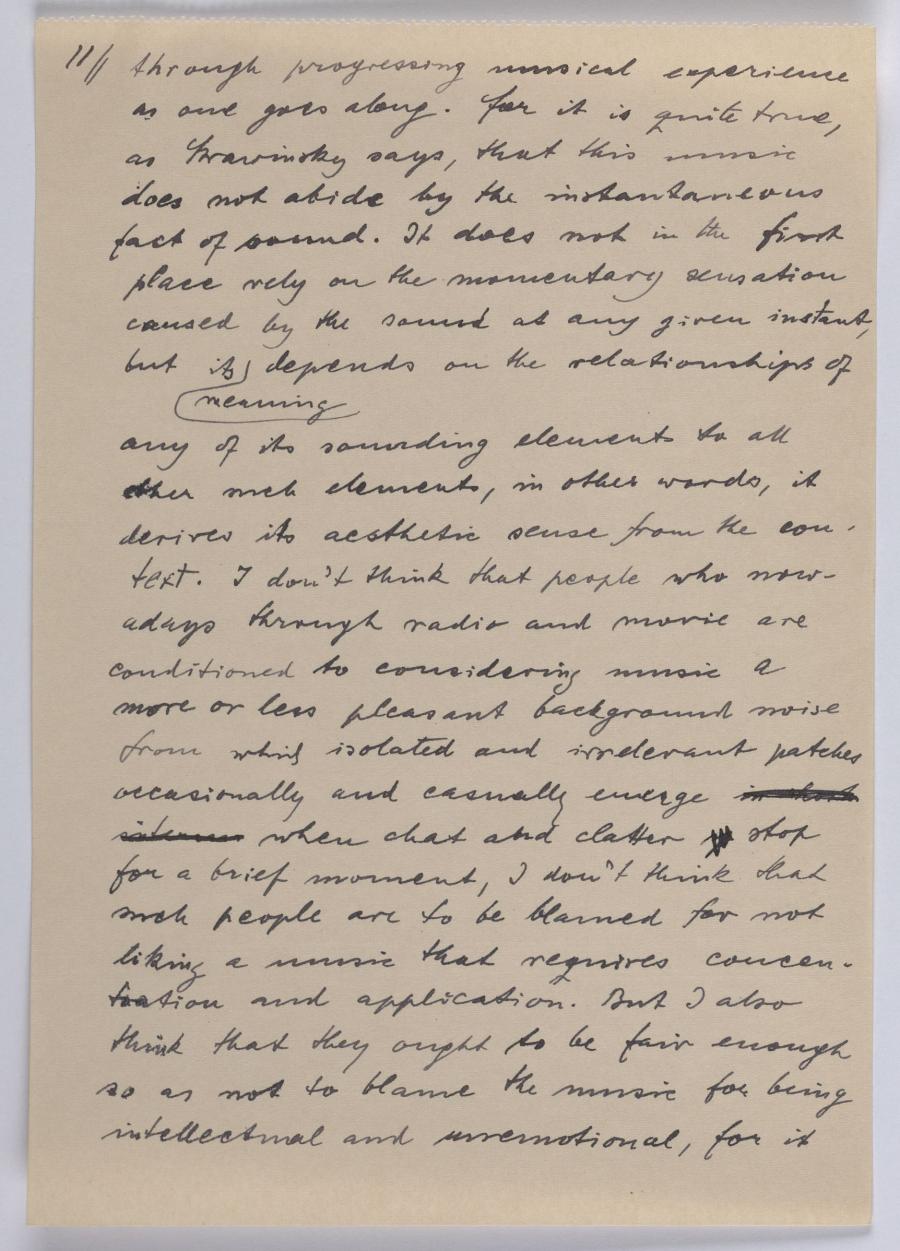

through progressing musical experience

as one goes along. For it is quite true,

as

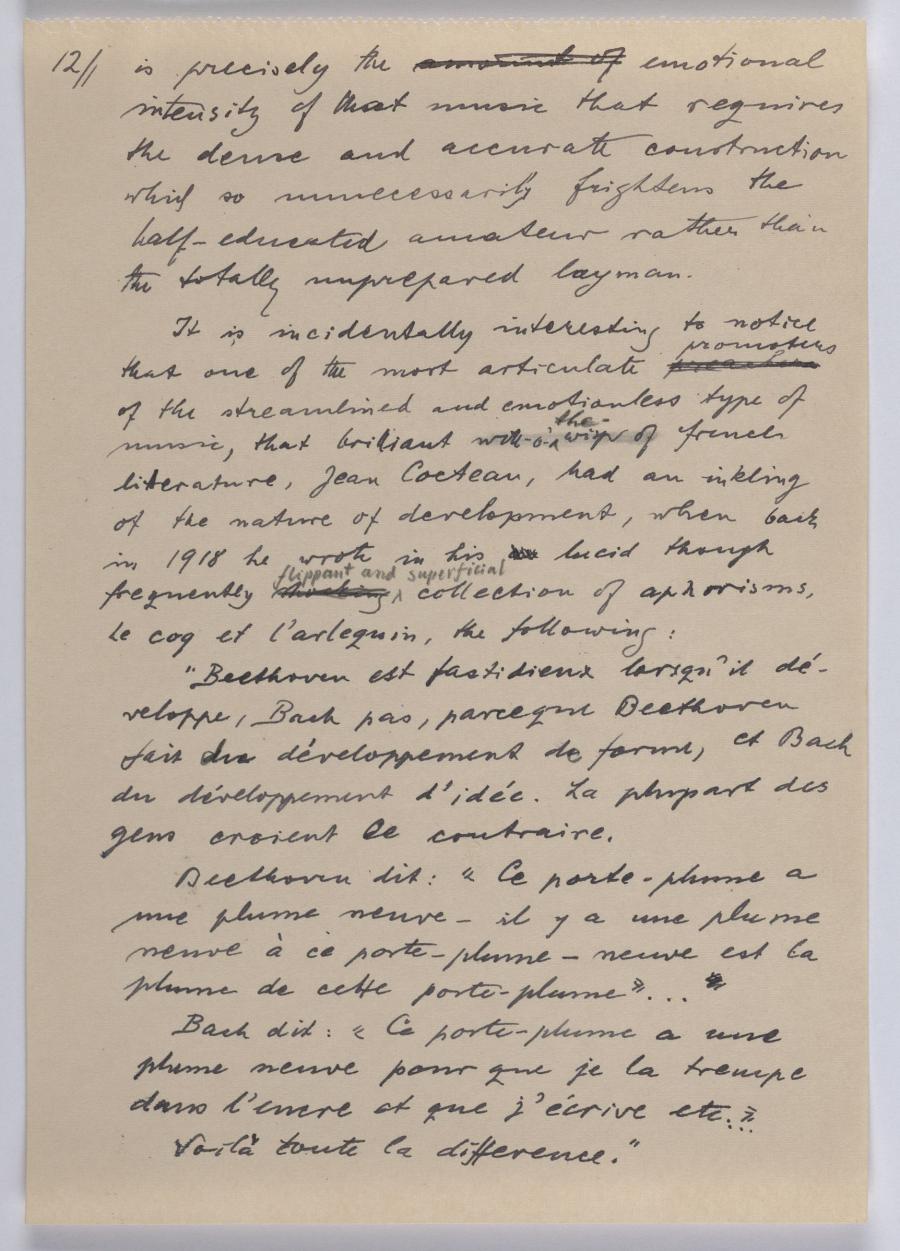

is precisely the

It is incidentally interesting to notice

that one of the most preachers shocking

"

Voilà toute la difference."

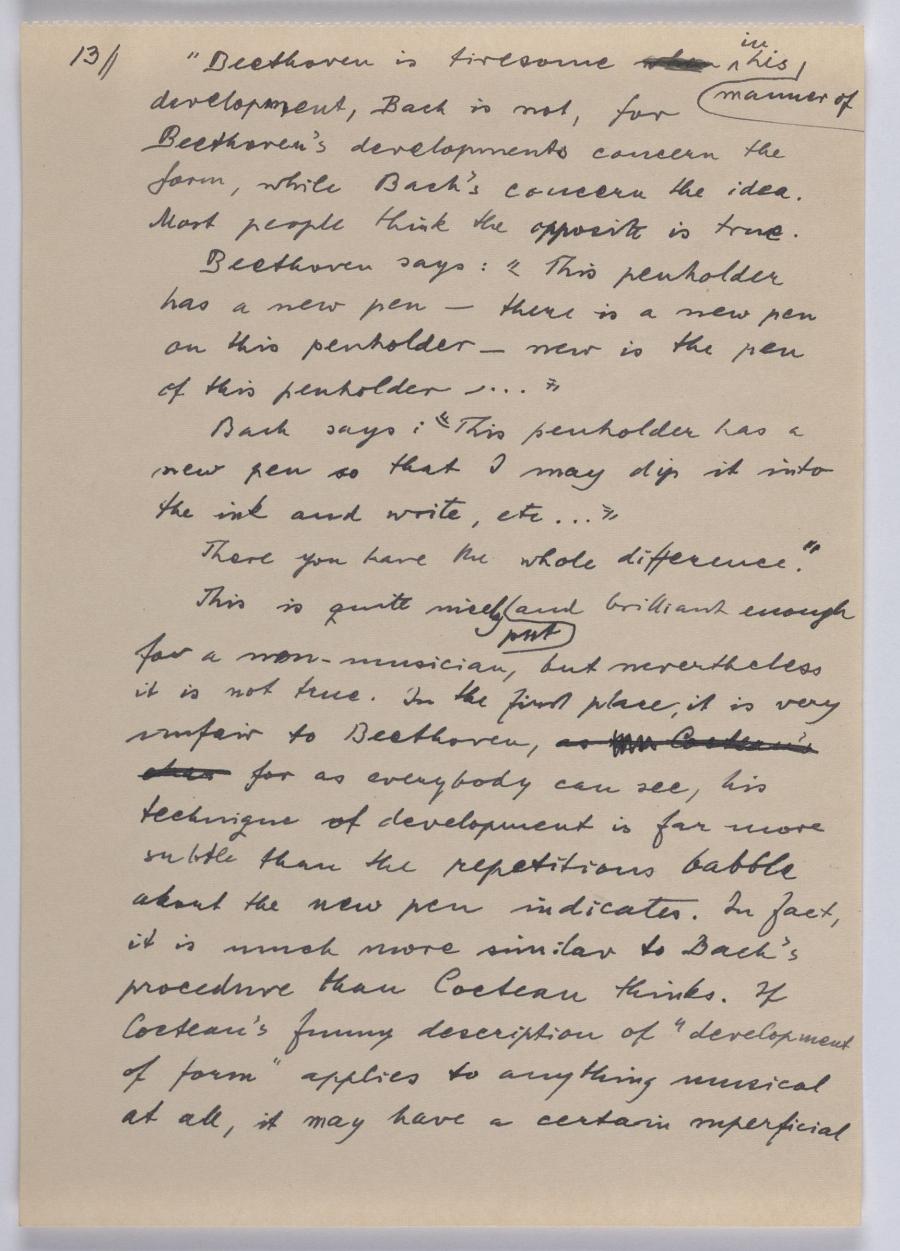

13//

"when

There you have the whole difference."

This is quite

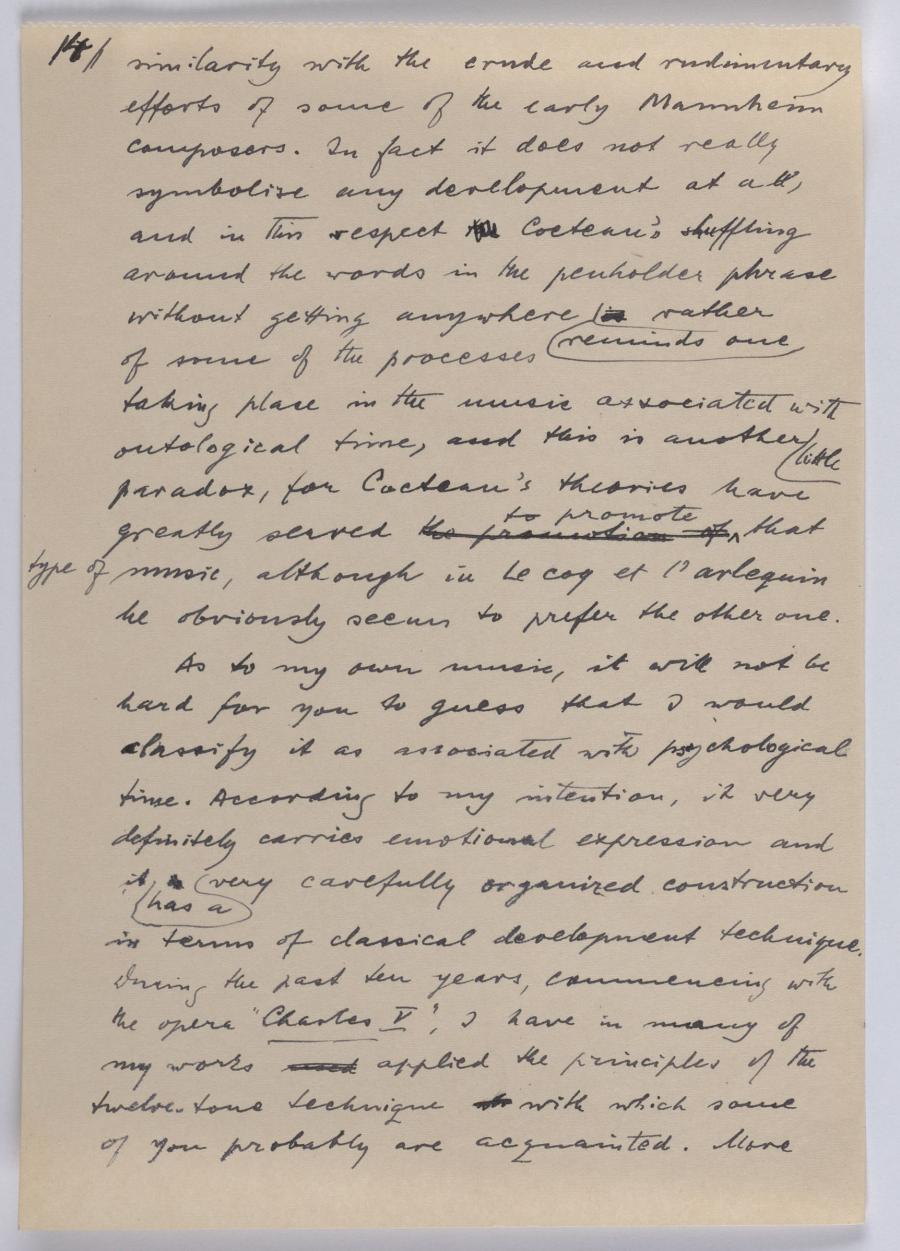

similarity with the erude and rudimentary

efforts of some of the early is ratherthe promotion of

As to my own music, it will not be

hard for you to guess that I would

classify it associated with psychological

time. According to my intention, it very

definitely carries emotional expression and

is Charles V"

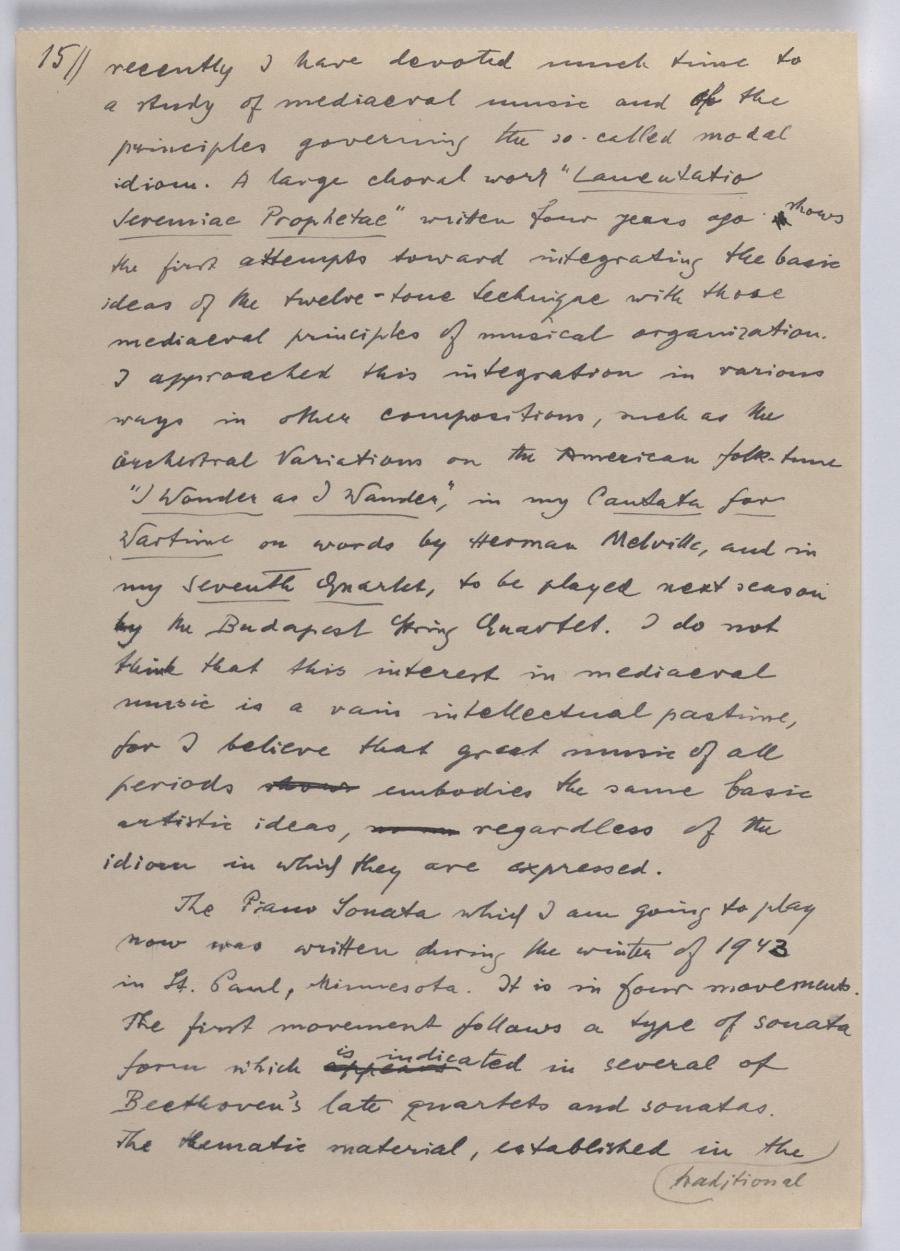

recently I have devoted much time to

a study of mediaeval music and of the

principles governing the so-called modal

idiom. A large choral work LamentatioJeremiae Prophetae"is I Wonder as I Wander", in my Cantata for Wartime on words by

Seventh

Quartet

, to be played next season by the Budapest String Quartet. I do not think that this interest in mediaeval music is a vain intellectual pastime, for I believe that great music of all periods

The appears

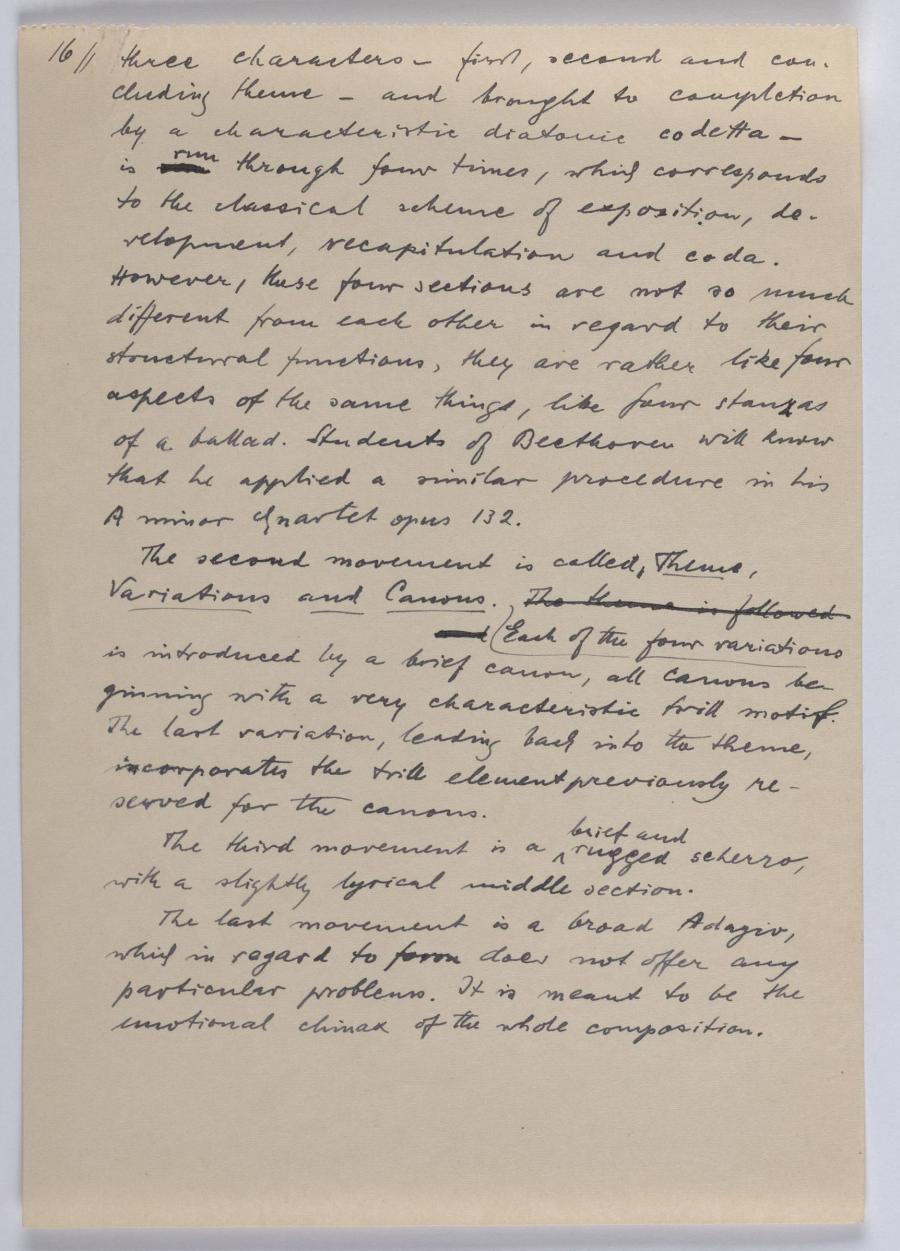

three characters - first, second and con-

cluding theme - and brought to completion

by a characteristic diatonic codetta -

The second movement is called, Theme,

Variations and Canons. and Each of the four varationsThe thema is followed

is introduced by a brief canon, all canons be-

ginning with a very characteristic trill motif.

The last variation, leading back into the theme,

incorporates the trill element previously re-

served for the canons.

The third movement

The last movement is a broad Adagio, which in regard to form does not offer any particular problems. It is meant to be the emotional climax of the whole composition.