A composer viewing this century's music. [UCSD Lecture III]

Abstract

Im Jänner und Februar 1970 war Ernst Krenek Regent’s Lecturer an der University of California, San Diego, wo er eine Serie von vier Vorträgen hielt unter dem übergeordneten Titel: „A Composer Viewing This Century’s Music“. Die Vorträge wurden jeweils Mittwoch abends gehalten und waren einer weit gespannten Themenpallette gewidmet.

Ernst Kreneks dritter Vortrag als Regent’s Lecturer an der UCSD, gehalten am 4. Februar 1970. In der ersten Hälfte des Vortrags setzt sich Krenek mit der Beziehung von Komponierenden und der Gesellschaft auseinander, und welche stilistischen Entwicklungen sich aus dieser Beziehung im Lauf der Musikgeschichte ergaben. Die zweite Hälfte ist vor allem ökonomischen Fragen und Problemen der Komponierenden im 20. Jahrhundert gewidmet.

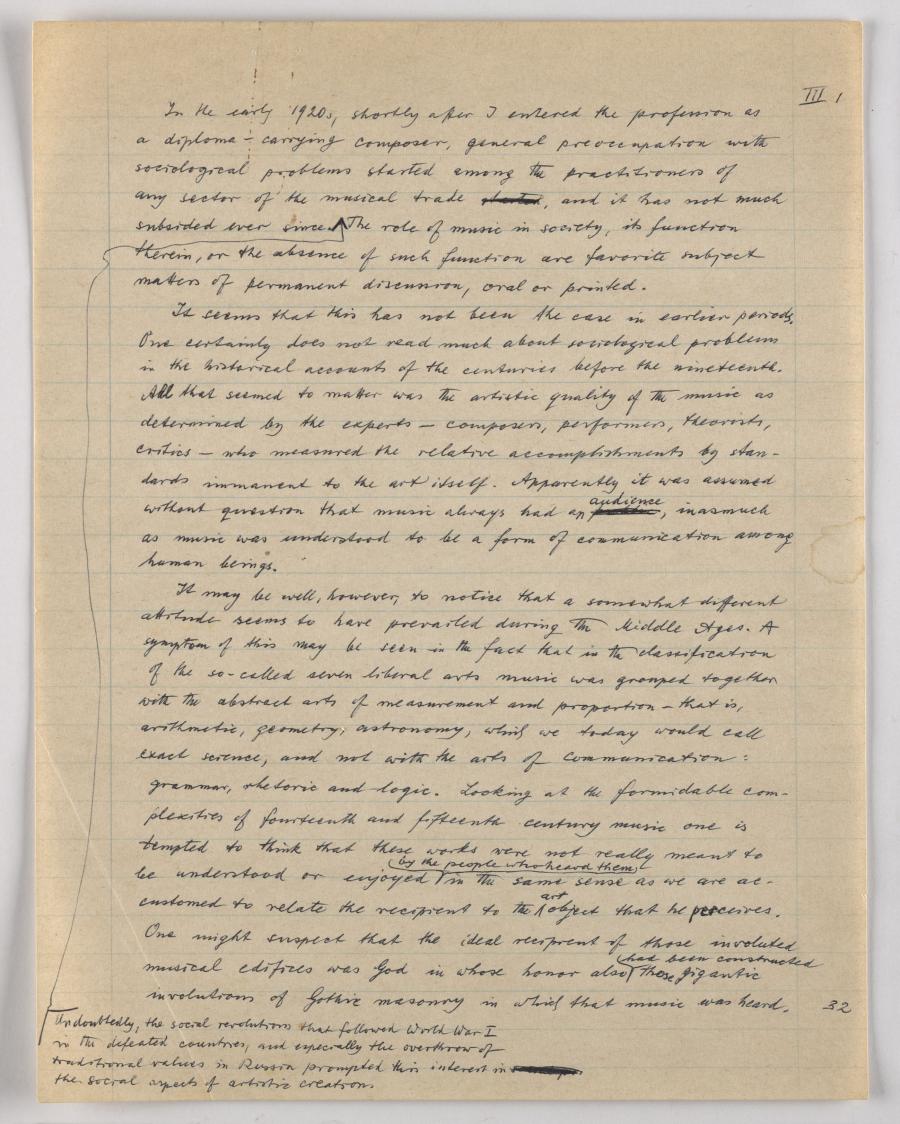

In the early 1920s, shortly after I entered the profession as

a diploma-carrying composer, general preoccupation with

sociological problems started among the practitioners of

any sector of the musical trade

It seems that this has not been the case in earlier periods.

One certaily does not read much about sociological problem

in the historical accounts of the centuries before the nineteenth.

All that seemed to matter was the artistic quality of the music as

determined by the experts - composers, performers, theorists,

critics - who measured the relative accomplishments by stan-

dards immanent to the art itself. Apparently it was assumed

without question that music always public

It may be well, however, to notice that a somewhat different

attitude seems to have prevailed during the Middle Ages. A

symptom of this may be seen in the fact that in the classification

of the so-called seven liberal arts music was grouped together

with the abstract arts of measurement and proportion - that is,

arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, which we today would call

exact science, and not with the arts of communication:

grammar, rhetoric and logic. Looking at the formidable com-

plexities of fourteenth and fifteenth century music one is

tempted to think that these works were not really meant to

be understood or

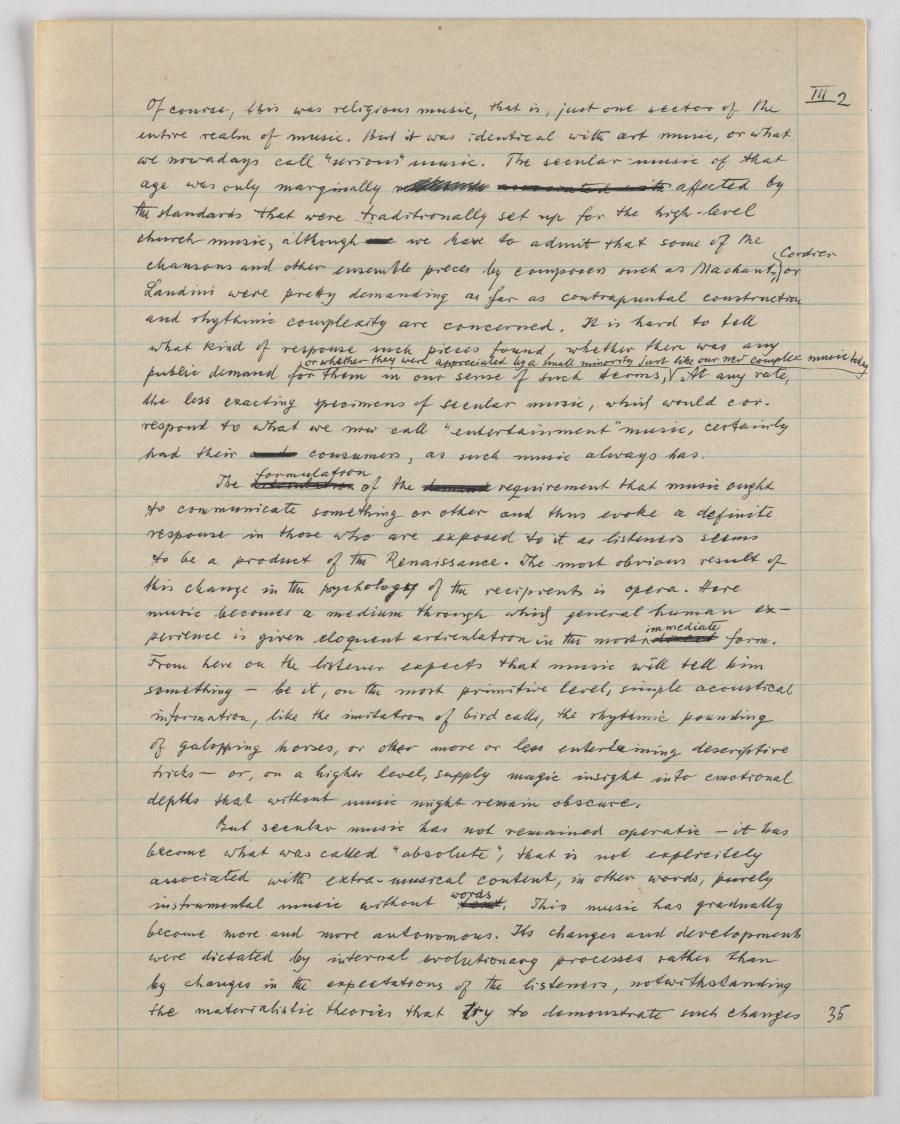

Of course, this was religious music, that is, just one sector of the

entire realm of music. But it was identical with art music, or what

we nowadays call "serious" music. The secular music of that

age was only marginally

articulation demanddirect form.

But secular music has not remained operatic - it has

become what was called "absolute", that is not explicitely

associated with extra-musical content, in other words, purely

instrumental music text

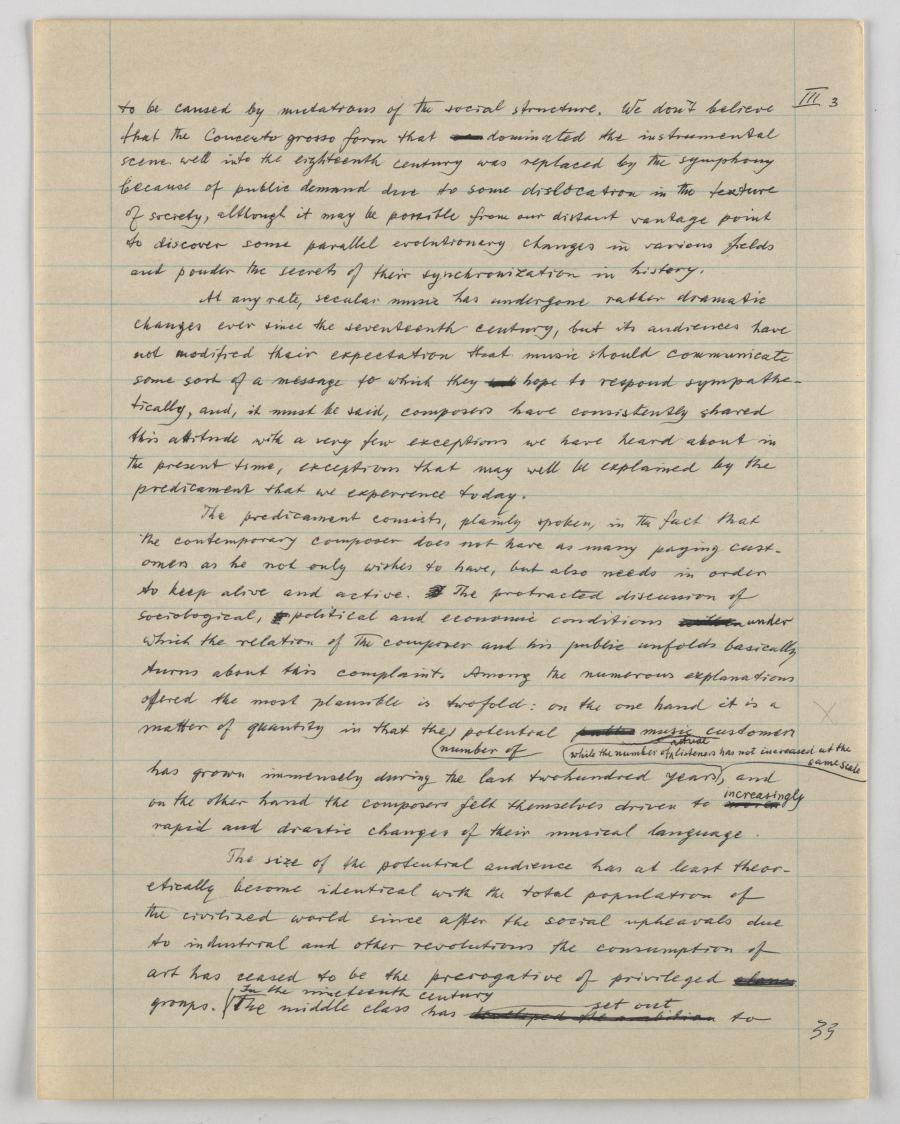

to be caused by mutations of the social structure. We don't believe

that the Concerto grosso form that

At any rate, secular music has undergone rather dramatic

changes ever since the seventeenth century, but its audiences have

not modified their expectation that music should communicate

some sort of a message to which they

The predicament consists, plainly spoken, in the fact that

the contemporary composer does not have as many paying cust-

omers as he not only wishes to have, but also needs in order

to keep alive and active. public musicmore

The size of the potential audience has at least theor-

etically become identical with the total population of

the civilized world since after the social upheavals due

to industrial and other revolutions the consumption of

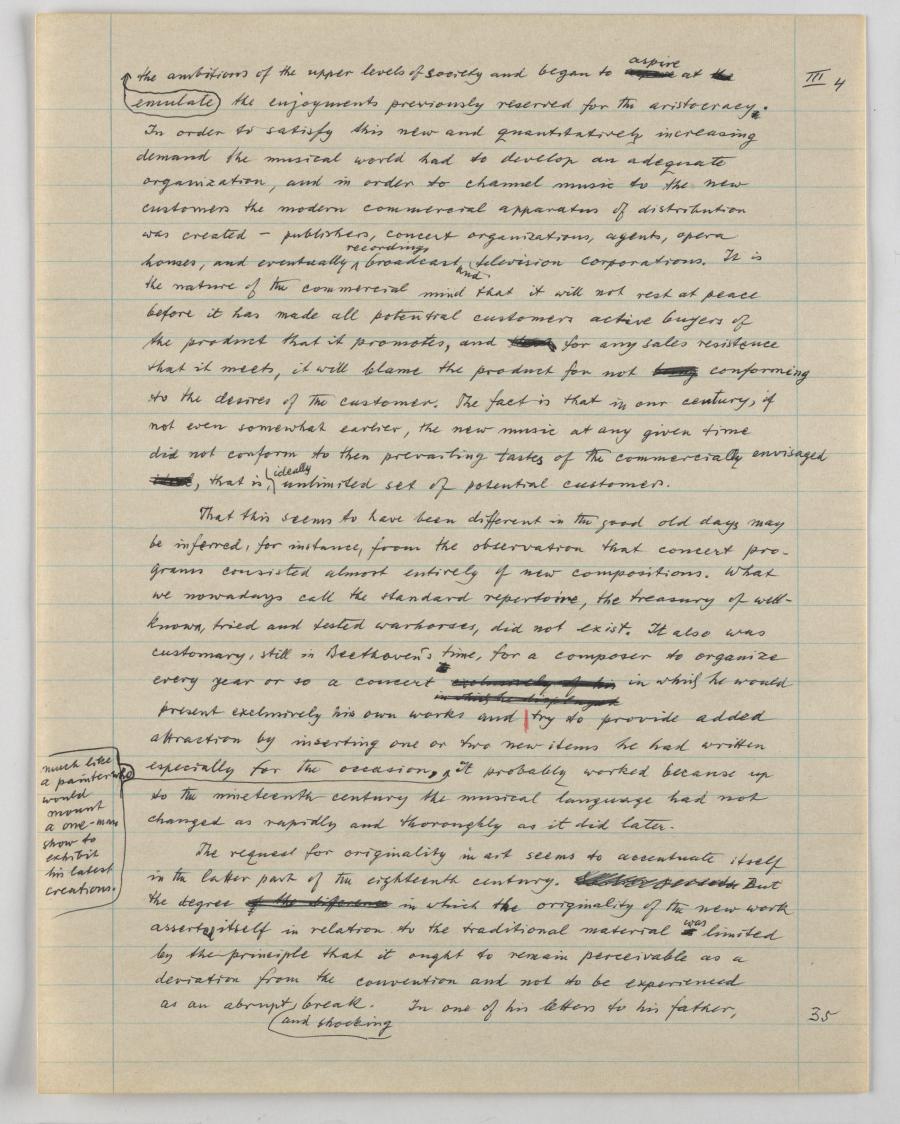

art has ceased to be the prerogative of privileged developed the ambition to

aspire the,.ideal, that is,

That this seems to have been different in the good old days may

be inferred, for instance, from the observation that concert pro-

grams consisted almost entirely of new compositions. What

we nowadays call the standard repertoire, the treasury of well-

known, tried and tested warhorses, did not exist. It also was

customary, still in exclusively of his in which he displays

The request for originality in art seems to accentuate itself

in the latter part of the eighteenth century. is

As the nineteenth century went on, connoisseurs of such cap-

acities were found less and less in a steadily growing general aud-

ience. Eventually such perspicacity limited

The composer frequently comforts himself by rationalizing

that he is ahead of his time, that the mentality of the public at large

will eventually catch up with him. This way of thinking is supported

to some extent by historical evidence. The progressive composers

and critics love to quote gleefully devastating contemporary

reviews in writers

denounced as point out formulated

Attempts toward making modern music a matter of

the present instead of the future were made during the period of

neo-classicism, between 1920 and 1940 approximately. Especially

in Gebrauchsmusik, music for use,

gained many followers. It was based on the idea that serious

music had become an object of passive admiration rather than

of vital concern, that it had alienated the public by requiring

it to marvel at its high-brow complexities. The new trend

was toward music-making instead of listening to it. Consequently

a type of music was promoted that would be easy enough

to be handled by a moderately equipped layman, "Spiel-

musik", that is music for play, geared to the capacities and

tastes of communities of juveniles, such as boy-scouts and

others, their tools being recorders and guitars. These people

were fiercely anti-romantic and despised any music written

between

the good old days when society was one big happy family and the

lion lying down with the lamb. As an example of such paradi-

saical conditions they liked to quote

The revival of the Concerto Grosso style was based on the

same wishful thinking that by restoring the outward appearance

of seventeenth century music one could also restore the supported appel sounds

Couriously enough adventures

vanced music was not much better received in the so-called free

world. It was tolerated, but not welcome.

Not that the attitude of the famous general audience, the

mass of customers had changed. But within the profession, among

the composers, a total about-face took place. The new generation of

young composers were not any longer interested in the

folkloristic or neo-classical exercises of their predecessors.

They had discovered my its less overboarding

of the non-aggressive art, they are usually very disappointing in terms of intellectual or any other interest.

Let us now take a look at the machinery only in 1790. and

Prior to the establishment of this principle and the setting

up of the organisations necessary to enforce it the composer

was usually compensated for his labors by a one-time fee

But It was also Again One

Only in our century the idea of the Copyright has found

general, if reluctant recognition. is curious,and heat, y store

Obviously it is impossible for the individual composer to

control innumerable, or even a few performances of his

works in five continents. arround

society societies were formed in the various countriesseven been acknowledged by all of them that working

In order to have performances to be controlled by his

performing right society, the composer's music must be avail-

able to prospective interpreters, and this is where the publishers

enters the picture. He is in a difficult position because

even the most successful composer will inevitably feel that

his publisher has not done enough for his work. Especially observes more prosperous

By the way, the notion that the publisher disposes of in-

credible, perfectly magic powers also exists in the heads of these

adversaries of new music who firmly believe that there is a con-

spiracy of critics, agents, interpreters, broadcasters and what not

nursed and maintained with the inexhaustible funds of male-

volent with seems be

The expectations which the publisher no copies would be

At any rate, the publisher does not own the work as an

art dealer does. It is entrusted to him for exploitation, and the

composer depends for his income on that exploitation. Nowadays

the main vehicle for making the musical work a source of income

is the public performance with admission fee. In the old days

the sales of printed copies, in the jargon of the trade somewhat

prominently Parsifal more than a hundredthousand copies were sold

during the composer's life time alone - which was just a few

years after the completion of the

tastic numbers may be accounted for by the aura of sensation that sur-

rounded the work, but the Parsifal score is difficult enough to scare

even present-day amateurs - if there were any who

Performances which have become the main source of revenue

as far as new music is concerned are then the main target of the

publisher's promotional activity. The established

concert institutions are not a very promising

hunting ground since their audiences still

demand the same fare as sixty years ago - or

at least the managers think so. At that time

we were told, as I remember, that the audiences

consisted of old people who were reluctant to

accept the dramatic innovations of new music.

In the meantime one or two new generations must have taken

the seats of those oldsters, and yet

As far as public performances go, opera productions are

the most rewarding financially, because opera houses are seating

lots of people, admission is relatively high and royalty percen-

tages adequate. In and of

act this music, they also cigarettes, hand lotion, cereals

As we know, there is a roundabout way of subsidizing art

through public funds, as long as private can channeled

[15]

keenly interested in the voting power of the masses of farmers that

produce those extra masses of wheat and butter. The makers of

symphonies and related items are very few, and they do not elect

the directors of the foundations that are willing to take care of the

surplus. It seems that there are quite a few people around who

are interested in listening to a new serial composition even by is

Howerer, for the last ten years or so, new music has gained an

in-position all over the world - not with the established institutions

but with a new layer of in-between agencies: festivals, private

associations, small groups of performers and listeners at colleges,

radio stations and so forth. I feel that this is a very welcome

development, for it is by no means an axiom that any

and all music has to be demanded and digested by all people,

just as not every book published has to be read by everybody

in sight. To call this minority of appreciative listeners an

Even so, their numbers are growing. Superficially looked

at, our period seems to show a bewildering array of com-

pletely heterogeneous musical styles. Actually, since 1945 a

new international style has become more and more pronounced.

shows reveals that

automatically becomes more palatable and acceptable to a growing number of recipients. Thus our present silent minority may, as time goes by, eventually gain a quite different status. Then it will be time to look for something new.