[Text about the characteristics of composing electronic music based on given examples of "Spiritus Intelligentiae, Sanctus" and "Tape double" written by Ernst Krenek for the magazine "Talea" of the mexican University UNAM]

Abstract

Für die März-Ausgabe der Mexikanischen Zeitschrift Talea beschrieb Ernst Krenek seine Beschäftigung mit Komposition im elektronischen Medium. Die Erzählung reicht von seinen ersten Erfahrungen mit „Spiritus Intelligentiae Sanctus“, op. 152, über die parallel stattfindende Auseinandersetzung mit seriellen Verfahren, bis zur wachsenden Distanz zwischen seiner eigenen Anwendung der elektronischen Klängen und der jüngeren Szene von elektro-akustischen Künstlern.

Talea,

In 1954 I was invited by the Westdeutsche Rundfunk (West Germain Radio

Network) in

I decided to use this opportunity for further pursuing an idea that had

occupied my mind ever since the late forties. It was on oratorio in honor

of the Holy Spirit. The text where produced on

However, it was not only the new and unusual sounds that

aroused my keen interest as soon as I became acquainted with the

electronic medium. Like some other, younger composers s

2

from ancient music rather than to make up one of my own Missa L´ homme arméex 1

Resolution: ex. 2 The lowest voice moves twice, the top voice three

times as fast as the middle voice. If this setting in executed at a reasonable

tempo of [whole note] [quarter note]eighth triplet wholequarter note fvery easy to cut, this length of tape

splice

The

At that time I was not able to complete more than the first

section of the oratorio which ends with the confusion of languages after

the Tower of Babel episode in

When types of oscillators which can be found in the new installations of the synthesizer

3

type,

I realize

Be that as it may, this attitude, consciously or not, seems to take into

account some of the negative characteristics ascribed to the electronic

medium from its early days. The electronic sounds were criticized for being

rigid, mechanical, life- and "soul"-less and therefore unsuitable for making

vibrato,

unevenness of attack and decay, fluctuations of volume -, much has been done

to equip the electronic installations with devices that would allow imitation

of those human touches. Even so, in spite of the infinite variety of sound

production michanism

However, this circumstance does not need to stand in the way of using the electronic medium for the creation of ever to desirably "expressive"

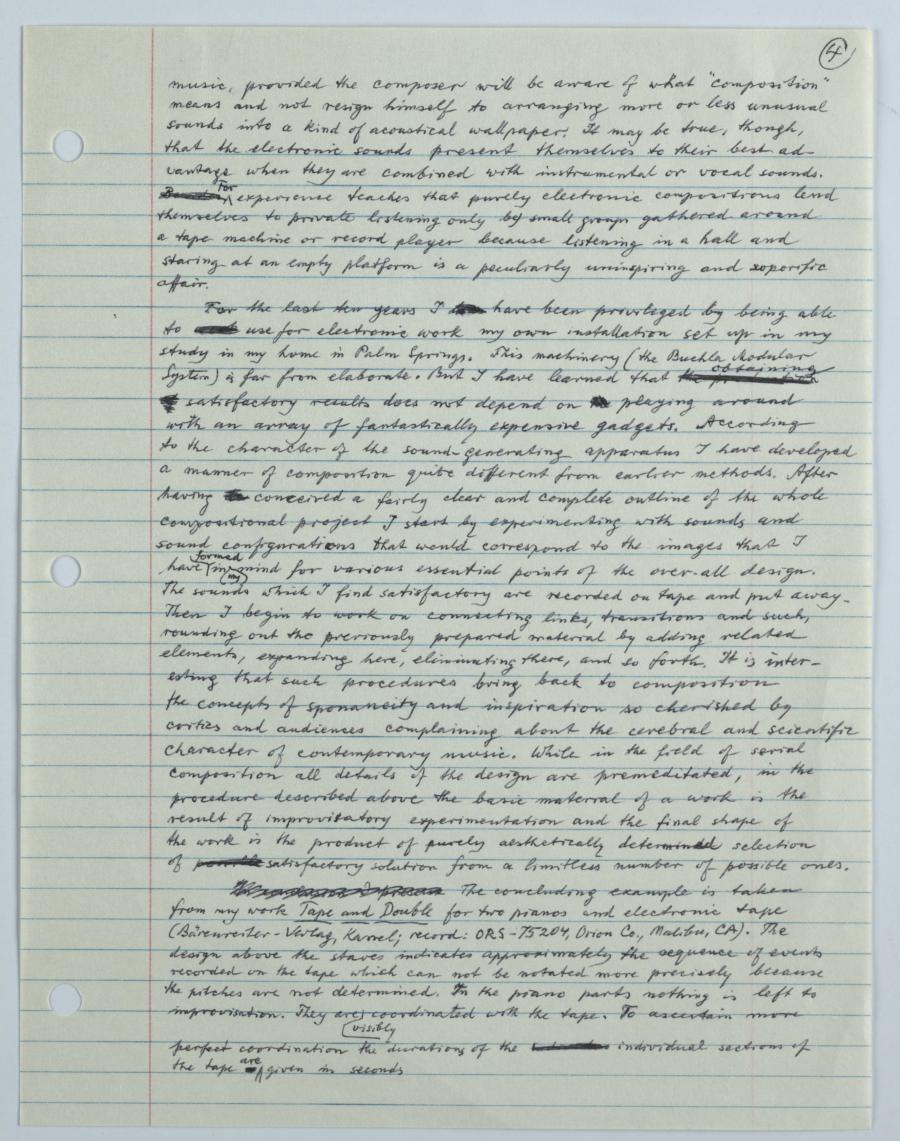

4

music, provided the composer will be aware of what "composition"

means and not resign himself to arranging more or less unusual

sounds into a kind of acoustical wallpaper. It may be true, though,

that the electronic sounds present themselves to their best ad-

vantage when they are combined with instrumental or vocal sounds.

Besides

For the last ten years I the production

Tape and Double for two pianos and electronic tapeis